Heldenplatz, Vienna, throughout the 20th Century

I finally opened the Vienna box--and almost couldn't stop, hence a first look at "Old Vienna"

Dear readers,

first of all, an apology for being somewhat “missing in action” these past few days. I’ve been quite busy finishing my book manuscript described in an earlier posting:

I am very happy, if not outright delighted, to report back to you that I’m done with it now; I’ve transmitted the manuscript (although the publisher—Taylor & Francis—requires a few more things to do, such as breaking down the manuscript in individual chapters, separate files for all illustrations, etc.) and I’m very pleased with the result.

At slightly over 100,000 words, my book will be both not excessively long (for comparison, it’s about the length of a Ph.D. dissertation in history, albeit in the good old fashioned way, i.e., a monograph and not a bunch of articles), and it will be fully “Open Access”. (Skip the sidenote if you don’t wish to learn about how academic publishing “works”[sic] these days…)

A Sidenote on “Open Access”

As per the de facto official (sic) definition, “Open access (OA) is a set of principles and a range of practices through which nominally copyrightable publications are delivered to readers free of access charges or other barriers”.

This means, in principle, that whatever business calculation went into publishing an academic piece of wort becomes—first and foremost, a question of offsetting production costs, book processing charges, etc., and it does so for both the author(s) and the publishers.

You can clearly observe the formation of two interrelated, if not inseparable, sets of (mainly perverse) incentives: for the publisher, if an author intends to have his or her work published “OA”, he or she better forks over some money; for the author, doing so might actually fast-track one’s work over others that are not “OA”-funded, i.e., still come with certain risks associated with it.

If, at this point, you’re thinking: well, since you’re talking academic books and articles, where would researchers obtain said funding? And here, dear readers, things get very odd, indeed—for the most part, these funds are coming from research funding /grant-awarding institutions, such as national research councils, foundations (mostly gov’t-funded).

So, if a scholar brings such “OA” funding, it means a subsidy for ostensibly private businesses (such as publishing companies) that no longer have to weigh the costs vs. benefits of producing this or that work; moreover, since most academic books are bought by university and college libraries (which are also mostly public institutions), this is a serious issue on any number of levels.

For you and me, this means that I can quote at some lengths from my own book in these pages, and I do intend to start here.

You see, for illustrative purposes, I went to the “Vienna” book of postcards (which I consciously didn’t do because I feared that, when I began, I would have a hard time stopping—and that’s just what happened) and looked for a specific theme, Vienna’s Heroes Square, or Heldenplatz.

So, please enjoy a few images from Vienna here.

Heldenplatz

For orientation, via Wikipedia:

Heldenplatz (German: Heroes’ Square) is a public space in front of the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria. Located in the Innere Stadt borough, the President of Austria resides in the adjoining Hofburg wing, while the Federal Chancellery is on adjacent Ballhausplatz…

After the Napoleonic War of the Fifth Coalition, the Austrian defeat in the 1809 Battle of Wagram and the Treaty of Schönbrunn, the remaining bastions of Hofburg Palace were slighted and replaced by a curtain wall with the—still preserved—Outer Castle Gate (Äußeres Burgtor). Inside the Hofburg walls, several squares and gardens were laid out, including the Volksgarten public park.

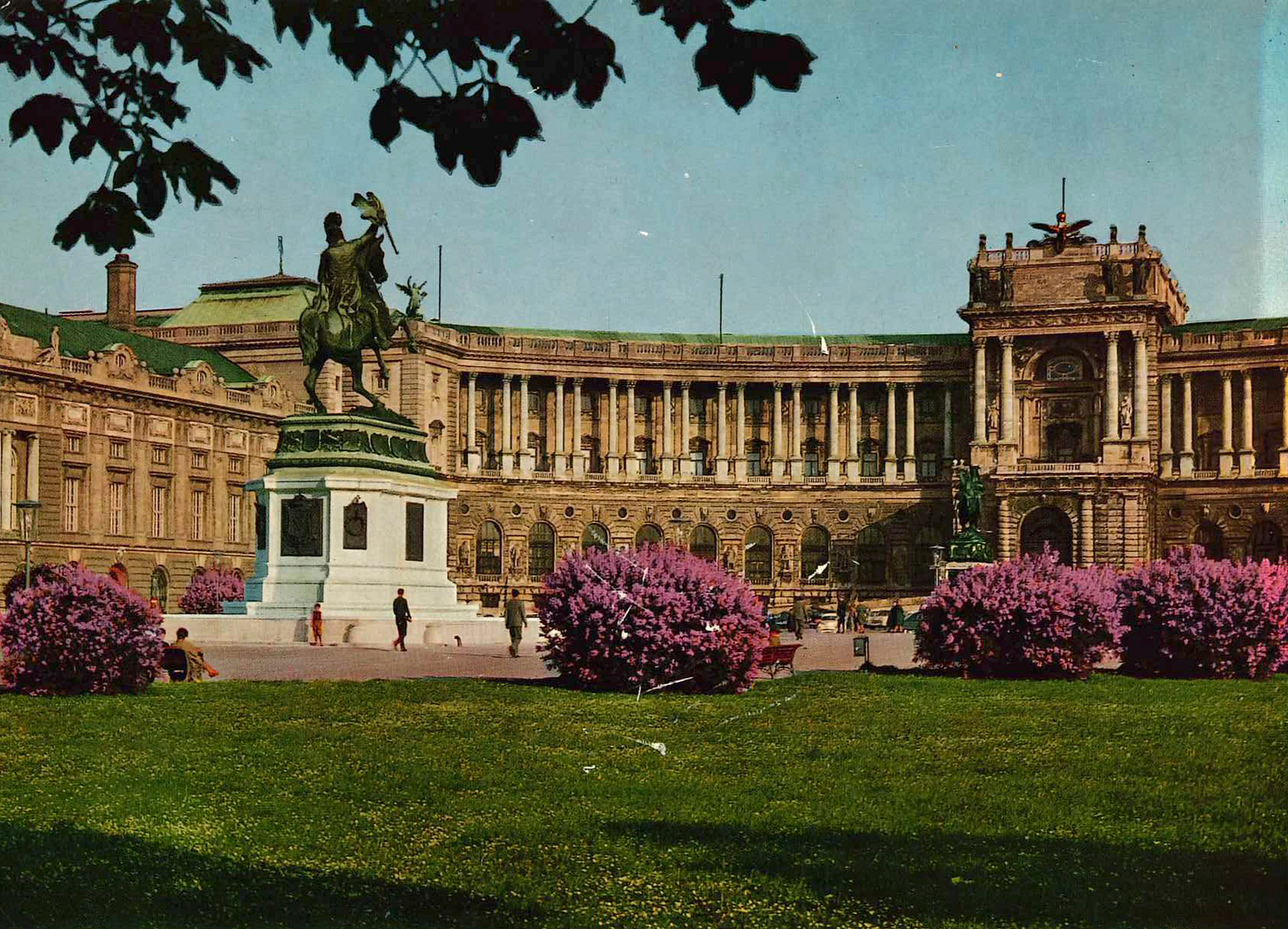

Below, a pre-WW1 postcard showing the Neue Hofburg, built around 1900; before it, two equestrian statues show Archduke Charles (he who defeated Napoleon in battle in 1809), with Eugene of Savoy in the rear (he commanded the imperial troops that defeated the Ottomans 1683-99).

Here’s a close-up of the equestrian statue of Eugene in front of the Neue Burg (undated, but it’s from before WW2):

If you got onto the roof of the Neue Burg and looked across Heldenplatz, this would be your view (in the 1950s, that is): the temple-like building on the left is the Parliament, the small temple in the centre is in the Volksgarten, and the tower behind it is City Hall.

Although undated, the postcard is from after the Second World War.

Heldenplatz in Colour

By the 1970s, the Heldenplatz looked like shown in these two postcards, with the below image depicting the entirety of the ensemble (with St Stephen’s Cathedral in the background on the left and the Heldentor in the foreground).

This is a long posting already, and I shall post a bit more about the Heldentor tomorrow.

I spent last year living on Wallnerstraße so this place was basically my front garden. One thing I will note is that your environment will play a large part on your overall mindset..... and I type this from my current environs which happens to be a soulless Dublin suburb.. District 1 in Vienna is a very special place... whether it was Michaelplatz or St. Stephens's it had a very positive affect on my overall mental state. St. Stephen's was next level... in terms of inspiration. The saddest part was conceding that we no longer have the stone mason's to replicate such beauty. I remained in a state of constant awe throughout my time in Vienna. You really got the sense it was the centre of an empire at one point. So many inspirational churches and cathedrals. Even the little Maltese church in the centre of town. I feel blessed to have experienced the place... being surrounded by architectural beauty is severely underrated...

Amazing architecture