All Souls

A few lines from my forthcoming book chapter, more about Erich Sonntag's life, and another of his poems

Once again, it is All Souls, and I was pondering how and what to post today for some time. Last year, I offered you a poem by Erich Sonntag, which I find deeply moving:

While it is tempting to simply re-post it, I wanted to do something else, in particular as a first academic article about the Erich Sonntag Postcard Collection will appear very soon™ courtesy of my friend Bruno Crevato-Selvaggi; it is based on the paper I presented last year at the Prato conference I related in June 2024:

So, instead of re-posting last year’s All Souls posting, I’ll be offering you a few paragraphs from my forthcoming article.

The below content is divided into two larger segments: first, I’ll provide a more refined account of Erich Sonntag’s life (1922-88), which in a way complements his self-authored C.V. (written in 1960) I found among his Bundesheer application files. In the second part, I shall provide another one of his poems that was apparently penned on the eve of his “baptism of fire” in August 1942. If compared—really: contrasted—with the poem ‘The Black Veil’ (see the above-linked All Souls posting from 2024), you can clearly see—read, feel—just how drastic the impact of war was (is).

Note that I’ve omitted the footnotes and other references for readability.

Who Was Erich Sonntag?

Born in 1922 in Vienna, he was raised by his divorced mother and grew up in relative precarity. Upon the Anschluss, he was eager to be drafted to the Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service) and Wehrmacht, in no small part to escape making decisions about his life. Upon basic training with an anti-aircraft artillery outfit as a communications specialist, Erich Sonntag was assigned to the Heeres-Fliegerabwehr-Abteilung no. 303 in summer 1942 and spent the next two and a half years on the Eastern Front. Eventually ending up in the Courland cauldron and cut off from German lines, he and the remnants of his unit were evacuated across the Baltic Sea on the night of 31 December 1944 to 1 January 1945. Erich Sonntag, whose life as a soldier had begun as a draftee, was eventually promoted to lieutenant towards the end of the Second World War and assigned to the artillery school in Rokitzan, a town in the former Sudetenland and today known as Rokycany, Czechia. It was there in the last days of the conflict that he and his remaining comrades surrendered to American forces of the 3rd Army commanded by George S. Patton.

Discharged from captivity shortly after the conclusion of hostilities, Erich Sonntag trekked back to his hometown of Vienna and reunited with his mother. Then and there, he also met his future wife, Maria Bauer, and began to put together his post-war life by briefly joining the Sicherheitswache, a paramilitary, if civilian, police outfit before getting married in 1947 and joining his stepfather’s bus company. While becoming a father of three in quick succession, he also obtained the necessary credentials to study at the university level and took courses in philosophy, only to have his life turned upside down once again when his stepfather’s company went bankrupt. Erich Sonntag subsequently worked all kinds of odd jobs, including as a storage worker, tutor (orig. Erzieher), and teacher at a Catholic school before, in 1961, he put on the uniform again and joined the Bundesheer as a 2nd Lieutenant (Oberleutnant) on 3/4 July 1961. Given his prior service and combat experience, he was assigned to the Anti-Aircraft Artillery School (orig. Fliegerabwehrwaffentruppenschule) as an instructor, and he remained a soldier until he retired in the early 1980s with the rank of a colonel. As his personnel file shows, particularly several assessment forms, his rise through the enlisted ranks—he was promoted to major in 1967, lieutenant-colonel in 1972, and colonel 1977—was due to a combination of high personal standards, integrity, and excellence; this is further borne out by the award to Erich Sonntag of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria (orig. Goldenes Ehrenzeichen) in 1980. He retired in October 1982.

Given his life and career, there exists a wealth of evidence that allows for a relatively dense reconstruction of the man behind the postcard collection. Speaking generally, the available sources fall into three categories: first, official government records from both Austrian and German public administrations, which are mostly preserved in the Austrian State Archive, including his afore-mentioned personnel file and the remnants of the military (Wehrmacht) and civil (Gauakten) files. Second, thanks to his life-long commitment to keeping track, there exists a sizeable amount of personal papers, which include autobiographical fragments—which I have christened Erinnerungen, or Memories/Memoirs—covering the period from January 1937 through 1943 (written in the 1983/84), pocket calendars covering the years 1945 through 1986/87 replete with notes and commentary, and a separate folder in which he detailed all his journeys from 1933/37 through February 1987, as well as several photo albums and scrap books. Finally, and connected to the second category, Erich Sonntag also left a small oeuvre of fictional writings, consisting of several short stories and one-act plays, which remained unpublished; they are found among his personal papers in Vienna. In addition, he published a total of thirteen war-themed, deeply personal poems in an anthology dedicated to soldiers’ poetry in the twentieth century published in 1968 by the Austrian Veterans’ Association (Österreichischer Kameradschaftsbund).

“At the Brook Near Seredichi”

To consider the impact of war, we shall now turn to Erich Sonntag’s poem “At the Brook Near Seredichi” (orig. Am Bach bei Sereditschi), which consists of but a few lines that have, at first sight, not much to do with the matter at-hand but its author. Yet, Erich Sonntag’s detailed travel log indicates that Seredichi (Середичи), situated roughly in the middle of the presumed triangle Bryansk (Брянск)-Orel (Орёл)-Kaluga (Калуга) and approximately 330 kilometres south-east of Moscow was the site of his baptism of fire. His autobiography, or memoirs, afford this moment in summer 1942 a few lines (my translation):

Friday, 7 August: It seems that we are not needed yet. We are still lying around in peace in glorious weather, undisturbed by aircraft or artillery. The dull thuds of the artillery give us the opportunity to learn from Robert Heyer what a launch and what an impact is. Later, it is hard to believe that we did not notice such a striking difference right away.

Saturday, 8 August: Now we are moving forward [towards the front]. We are all getting a bit nervous. The closer we get to the sound of battle, the more we ask Robert if we’re not too close. The battery takes up a firing position near Seredichi.

Tuesday, 11 August: The big premiere: we are firing at aerial targets for the first time.

Friday, 14 August: We leave Seredichi and, travelling via Gordiana [likely Goryanskii (Горянский), due north of Seredichi], take up a position near Blienow [Beljow (Белев)]

While these few lines pale by comparison to later, more dramatic passages of Erich Sonntag’s recollections, the baptism of fire, and the subsequent artillery barrage, close combat, and use of the battery’s 8.8 cm anti-aircraft artillery against a Soviet attack spearheaded by several T-34 tanks—two of which were knocked out, he recalls, on 19 August 1942—left a profound impression on the then-20 year old young man. So much so, in fact, that he elected to include the afore-mentioned poem in the anthology a quarter-century later; hence, I shall reproduce it here in both its German original and my translation:

At the Brook Near Seredichi

Waves

rush

gushing high.

Across the stones

tiny water droplets

still roll.

Silver spring

sprinkling, swiftly

thy water splashes away.

Green grass,

glistening and soggy,

stands on the banks there.

And on swift

small ripples

the years hasten by.

Rushing brook

beneath leafy green!

That’s what came to mind!

Am Bach bei Sereditschi

Wellen

schnellen

gischtend hoch.

Über Steine

rollen kleine

Wasserperlen noch.

Silberquell

springend, schnell

zischt dein Wasser fort.

Grünes Gras,

glänzend und naß,

steht an den Ufern dort.

Und auf schnellen

kleinen Wellen

eilen die Jahre dahin.

Rauschender Bach

unter laubgrünem Dach!

Das kam mir so in den Sinn!

The reason for reproducing this episode in this section is perfectly obvious to this author: it is, in fact, impossible to separate the life and experiences of the collector from either his personal and fictional writings, nor from Erich Sonntag’s postcard collection. Whatever the aesthetic and literary qualities of this young man’s poem (or my translation, for that matter), it marks a profound moment in his biography: although not the profession of his choosing, Erich Sonntag was, first and foremost, a soldier, first in the Wehrmacht during the Second World War and, from summer 1961 onwards, in the Austrian Armed Forces.

Coda: All Souls

If, at this point, I’m interrupting the flow, it is because I wish to wrap up this All Souls posting with a few more lines about the impact of war.

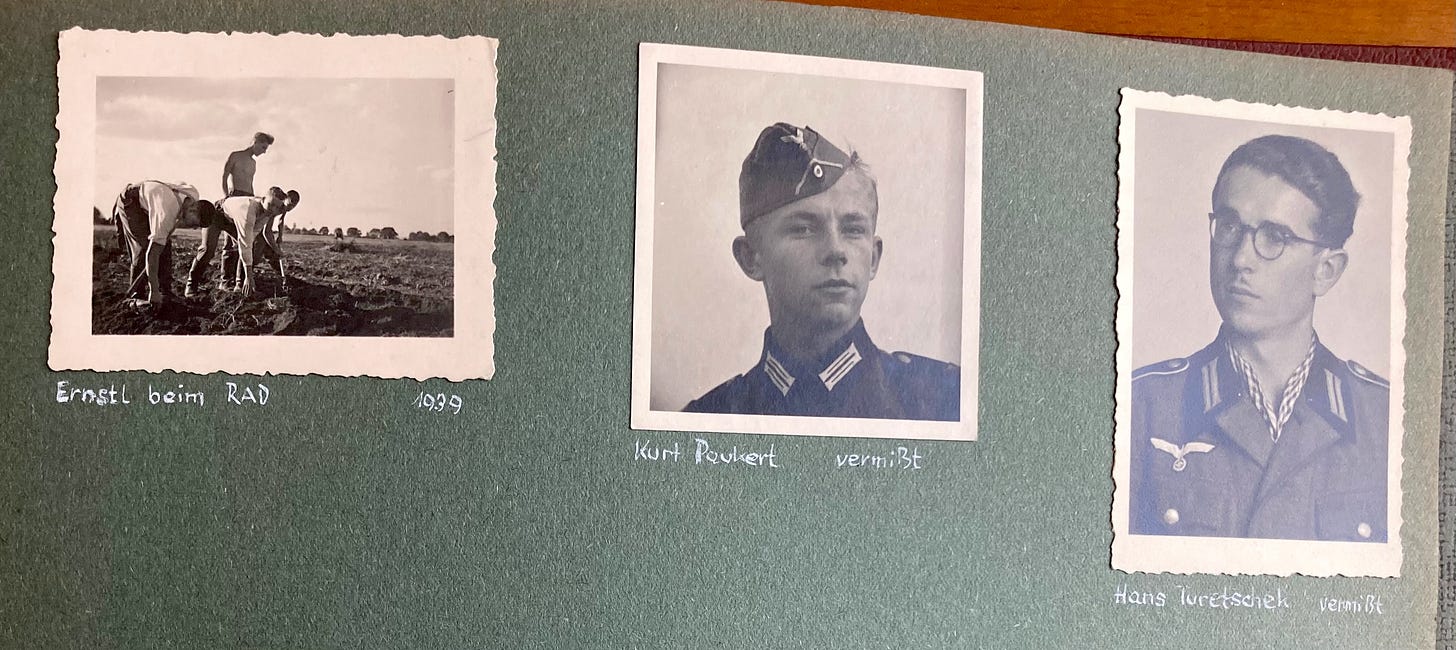

You see, Erich Sonntag left a few photo albums (“scrap books”), and I’m adding the last page of his album entitled “War Memories”, orig. Kriegserinnerungen, to drive home the eternal pity of war:

Shown are, from left to right, “Ernstl”, Erich Sonntag’s best friend from his days as a gymnasium student; he was drafted into the Luftwaffe and trained as a pilot, and he was shot down over the Black Sea in summer 1942.

The other two images show two of Erich Sonntag’s closes schoolmates, Kurt Paukert and Hans Turetschek, both are referred to as “missing in action”, or vermißt.

Putting these images up serves but one purpose: to lament the eternal suffering of those—all—who remained in the field. Erich Sonntag carefully curated his photo albums long after the war as the war left a lasting impression on him and everybody else.

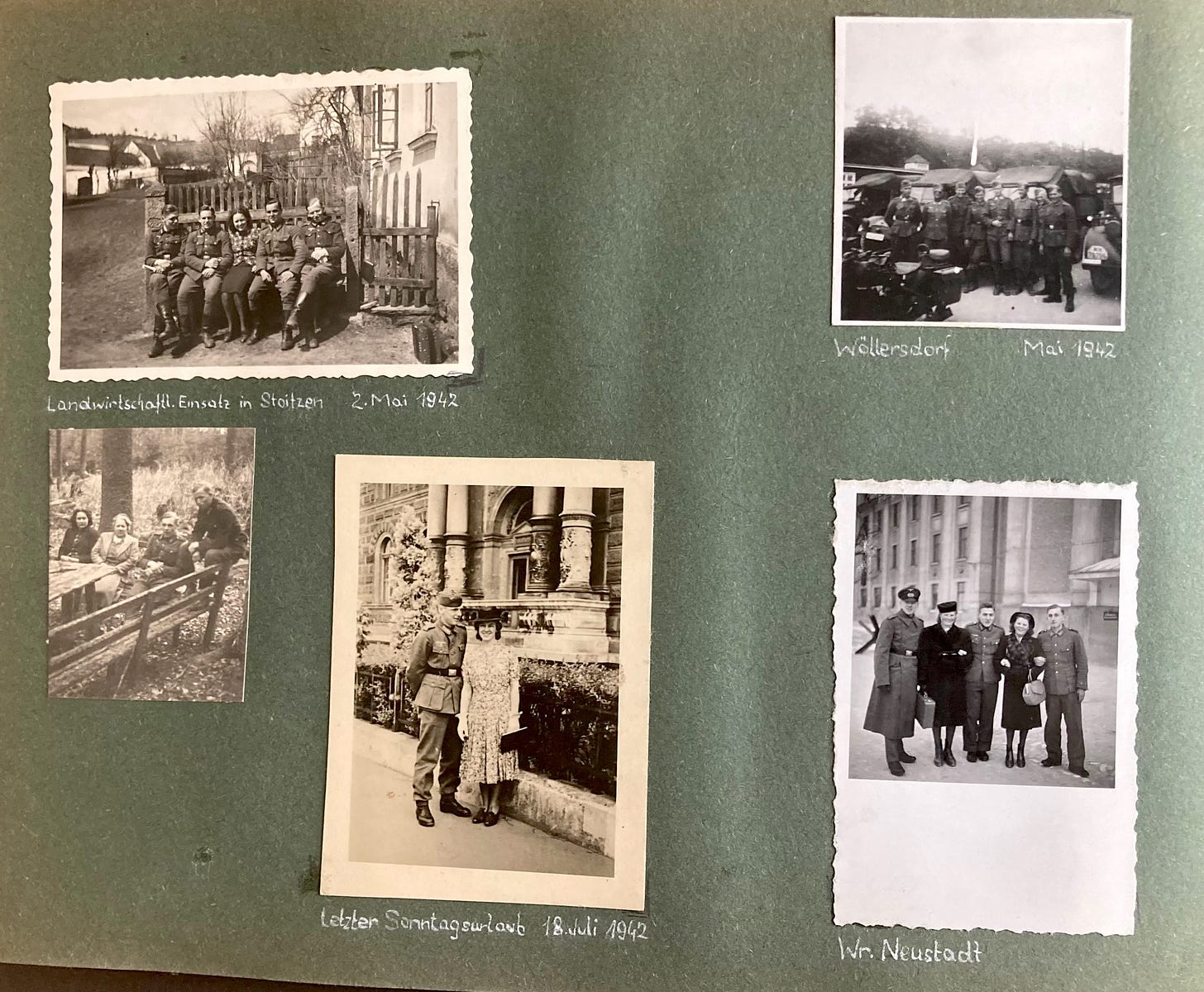

If you’d contrast last year’s All Souls posting, specifically the dark poem, with the ditty about the last moments before Erich Sonntag’s combat experience began, the last page in his photo album before the photographs from the Eastern Front tells a very different “story”:

On the top-left picture, Erich Sonntag is seen during his basic training—when his unit was “deployed” to help out local farmers during the harvest season (dated 2 May 1942); in the lower half, the middle picture shows a young Erich Sonntag a few days before his deployment to the Eastern Front with his mother (dated 18 July 1942).

It is in this context that the poem “At the Brook near Seredichi” speaks, I would argue, very clearly to this particular day.

Rest in peace.

Danke, Epimetheus, für diesen Einblick in Deine Familiengeschichte.

I'm a few days late reading this post but I wanted to say I was moved by the poem and the diary accounts, not least the photographs, especially his mates who didn't return. The way things are being manipulated for another repeat leaves me very disillusioned for the future of mankind. Your grandfather died fairly young too, but he recorded his life and now, his historian grandson publishing, for posterity. Thank you.