Nostalgia for…Old Berlin? For Germany? Which one? And: what for?

Notes on a chat with my colleague Marcus Colla--and vintage postcards from (East or West?) Berlin

Earlier this week, I barged into my friend’s office to drop off something; we had a rather long-ish conversation. When I returned a day later, I was asked: “do you have 6:40 minutes?”—“I’ve also got 7, if needs be.”

Turns out, Marcus Colla is going to be in Berlin next week and presenting a 6:40 minute-long (sic) talk about Nostalgia. In the so-called Humboldt Forum, which eventually (delays and cost overruns included) the GDR’s “Palace of the Republic” (Wikipedia), which itself was a really existing replacement for the Berlin Palace, a.k.a. the Stadtschloss—the urban residence of the Hohenzollern dynasty—in downtown Berlin (also Wikipedia).

Marcus will be talking at this venue on 4 Oct. 2024, so if you’re in the area, why not consider attending? It’s going to be a blast, of this I’m sure—here’s a teaser from the program:

The struggle for East, West and all-German identity that began in the 1990s continues. The central question is: Who remembers the two German states, why and how? Even during the process of the GDR’s accession, East and West Germans engaged in heated discussions: in private encounters and in public, in parliamentary debates, newspaper commentaries, television shows and academia. Many commentaries critically diagnosed “Ostalgia”. The longing for the old Federal Republic, “Westalgia”, on the other hand, was hardly a topic.

I was listening to him presenting as a “trial audience”, and his slides were nice—but they lacked the particular *bang*. So I offered a few picture postcards, and he said he’s going to include him (I’ll take you at your word, Marcus).

And then I thought you might enjoy them, too. So, here goes.

The Berlin Stadtschloss Before WW2

Above and below, two picture postcards from after WW1—the one below was mailed in 1919, the other one, sadly, doesn’t come with a date.

Note that the Palace (Schloß) and Cathedral (Dom) are clearly visible in both images, and they point to the close, if not symbiotic, relationship between the Lutheran Church and the Prussian State; since the end of the monarchy in 1918, and perhaps even more so since the abolition of Prussia in 1947, the German Lutheran Church has been, well, quite…headless.

The GDR Takes Over

As is widely known, Berlin was occupied by the four major Allied powers and divided into four sectors (of which the three Western ones were eventually combined). So-called “West-Berlin” was a kind of enclave surrounded by the Communist German Democratic Republic of (which bestowed upon the former a certain, unreal character—and its politics was correspondingly surreal as they couldn’t do wrong, if only because there were no consequences not to upset the propaganda cart vs. the GDR).

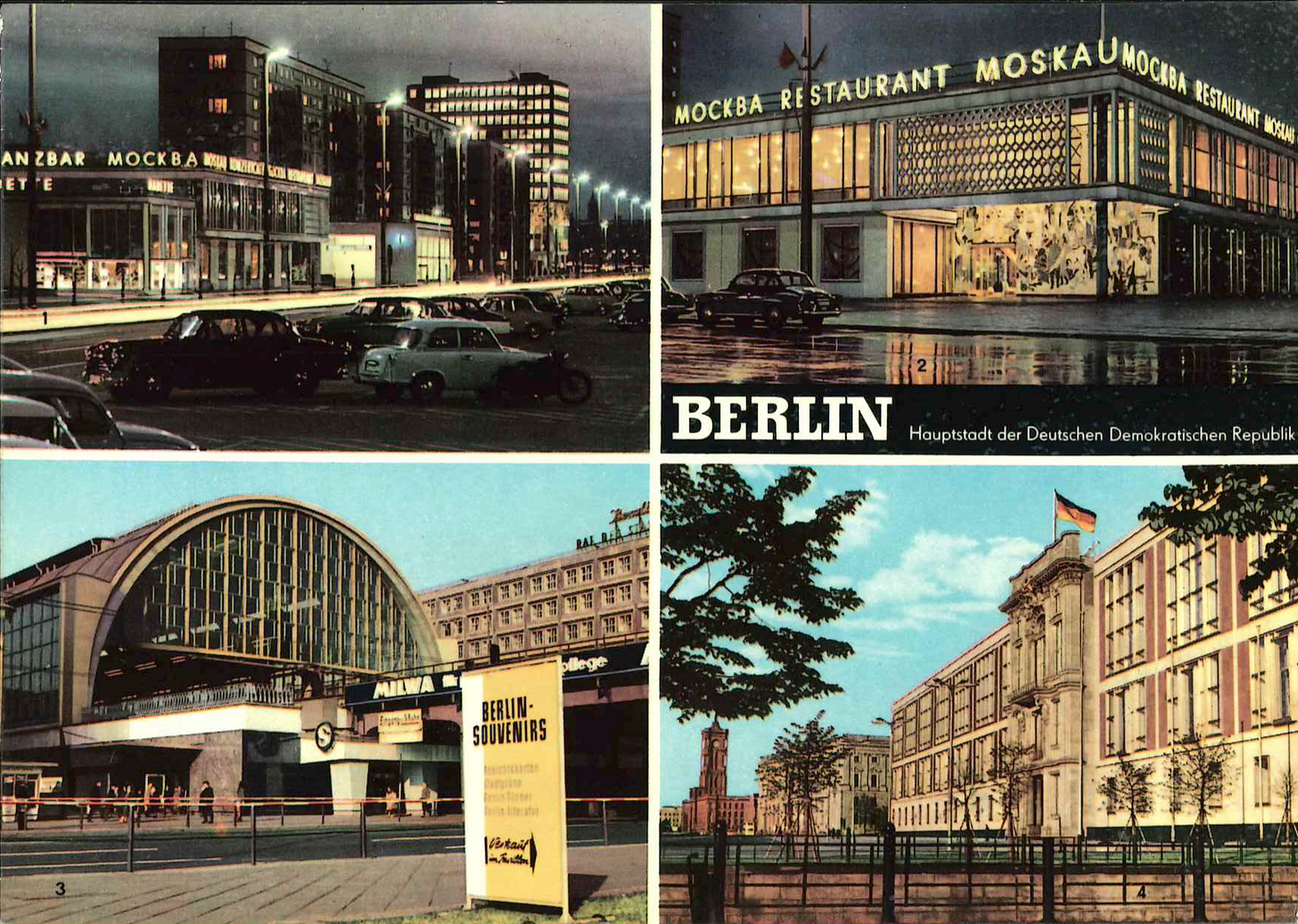

During WW2, Berlin suffered massively, including during the Soviet assault in spring 1945. The city centre was heavily damaged, both by Soviet troops and Allied—mainly British and US—bombers well before that point in time. The Stadtschloss was similarly hit, and the new East German authorities eventually demolished the remains in 1950. This explains why in the above postcard, entitled “Berlin—Capital of the GDR”, mailed in 1956, a lot of things are shown but not the city centre.

If the “city centre” (Zentrum) is shown, as in the above example, Berlin looks thoroughly un-identifiable, except for the huge transmission tower on Alexanderplatz. “Zooming” in, this is Alexanderplatz in the 1970s:

Moreover, sifting through the 170+ picture postcards Erich Sonntag categorised as East Berlin, one often finds additional, and very typical, images showing a certain brutalist modernity, such as the “International Commerce Centre” (Int. Handelszentrum) shown below.

Of course, (East) Berlin’s new architecture coexisted, rather uneasily, with the remnants of earlier times, such as the Brandenburg Gate (note the absence of the Wall, which allows for the dating to point to before its construction in 1961):

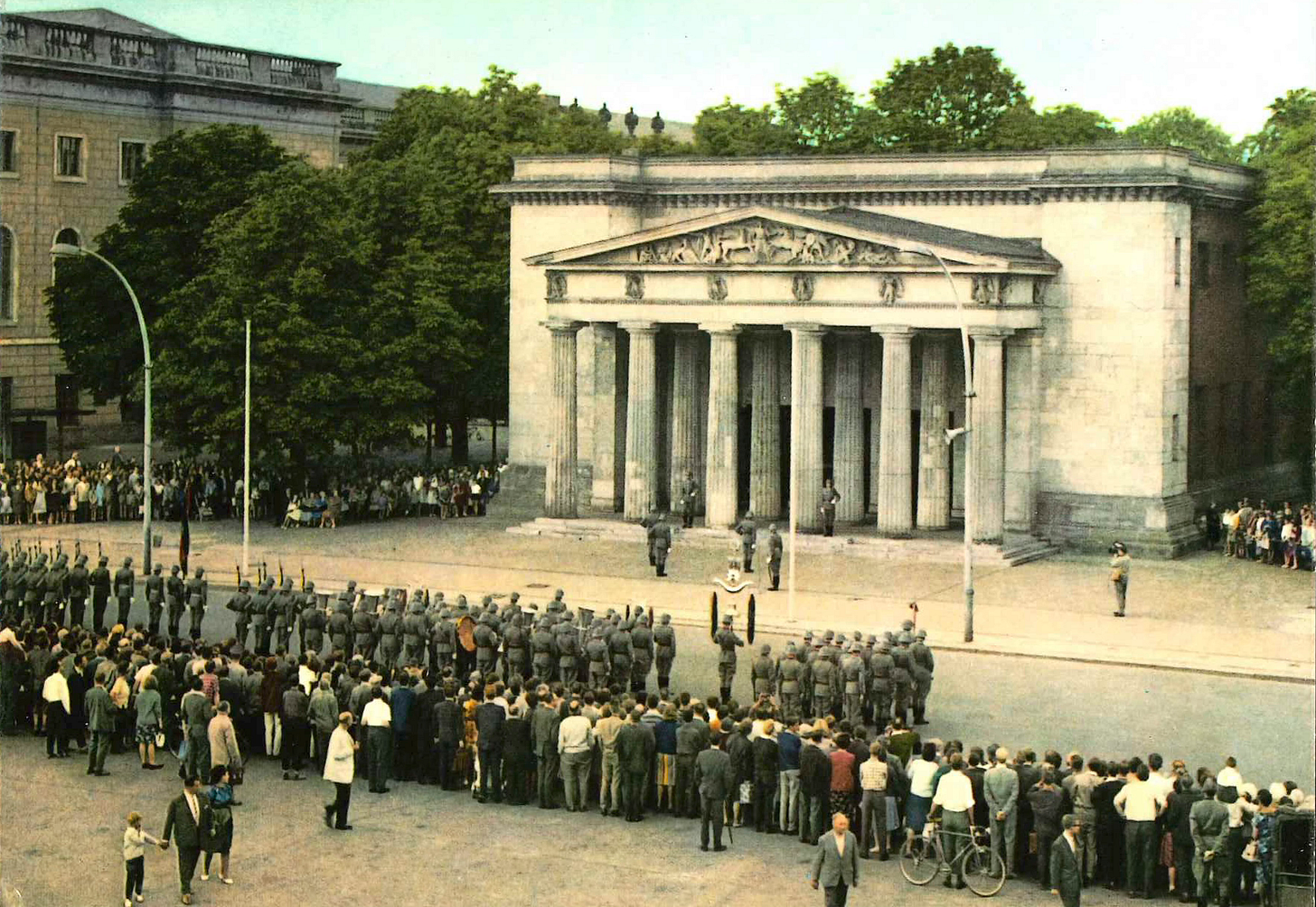

This feature is particularly striking on the below postcard, which shows “the changing of the guard at the Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism”—outside the Neue Wache on Unter den Linden, Berlin’s main boulevard.

I’ll also post one other postcards that shows a quite different perspective of East Berlin: a “Public Pool in Pankow”:

Erich’s Lampenladen

In 1945, Berlin lay in ruins, and what had remained of the Hohenzollern’s Stadtschloss was removed in 1950. In its stead, the new East German leadership decided to build a representative (ahem) building for its People’s Chamber (Volkskammer). From Wikipedia:

The new socialist government declared the Stadtschloss a symbol of Prussian militarism, although at that time there appeared to be no plans to destroy the building. Some parts of it were in fact repaired and used from 1945 to 1950 as an exhibition space…

Only one section was preserved, a portal from the balcony from which Karl Liebknecht had declared the German Socialist Republic. In 1964 it was added to the State Council Building, with an altered cartouche, where it forms the main entrance. The empty space where the Stadtschloss had stood was named Marx-Engels-Platz and used as a parade ground.

In the below postcard, you can see that State Council Building (Haus des Staatsrats) in the bottom right image; it includes that surviving “altered cartouche”:

From 1973 to 1976, during the government of Erich Honecker, a large modernist building was built, the Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic), which occupied most of the site of the former Stadtschloss.

Because of its…impressive architecture in such an auspicious location, the Palace of the Republic was colloquially known as “Erich’s Lampenladen” (or Erich’s Lamps’ Shop); this is what it looked in the early 1980s:

And here it is in all its “glory”:

And one more before we wrap this up:

Epilogue: the Reconstruction of…History?

The “Stadtschloss” has now been re-built and re-named the Humboldt Forum, and it is, as its website claims, “more than a museum”.

What, then, is the Humboldt Forum?

For possible answers, we return to Marcus Colla’s recent publication “The Present is History”, Central European History, 56, no. 1 (2023): 2-17. From the abstract:

From its very conception some thirty years ago, Berlin's Humboldt Forum has been one of contemporary Germany's most controversial cultural initiatives. One aspect of this controversy has been the role of the Prussian past in reunified Germany. Housed in a reconstruction of the Prussian Royal Palace destroyed by the East German communist government in 1950, the visual symbolism of the project spurred a long struggle over the appropriate urban aesthetic for the country’s capital city. In the view of many critics, the structure symbolizes the triumph of a particular conservative narrative of national memory that excludes the GDR, downplays National Socialism, and uncritically celebrates the Prussian past. This article traces how public debates about the structure of the Humboldt Forum have served as a vehicle for reflection on Prussian history and its relevance (or irrelevance) for reunified Germany.

Further into the piece, we find this:

At stake here were, on the one side, a critical perspective that held “Prussia” as a latent and ever-dangerous political force in contemporary Germany and, on the other, one that held Prussia’s “pastness” to be an irrevocable historical fact. On the margins, meanwhile, were those who continued to praise the Prussian state and champion the “virtues” that allegedly inhered within it. The Humboldt Forum, in other words, became something of a test case of whether Prussia could or could not, finally, be considered a “normal” part of German history.

I can only recommend reading the rest of the piece, esp. as the issue of how “true” the reconstruction should be included a number of…rather strange and very particularly German considerations (I’ve omitted the references):

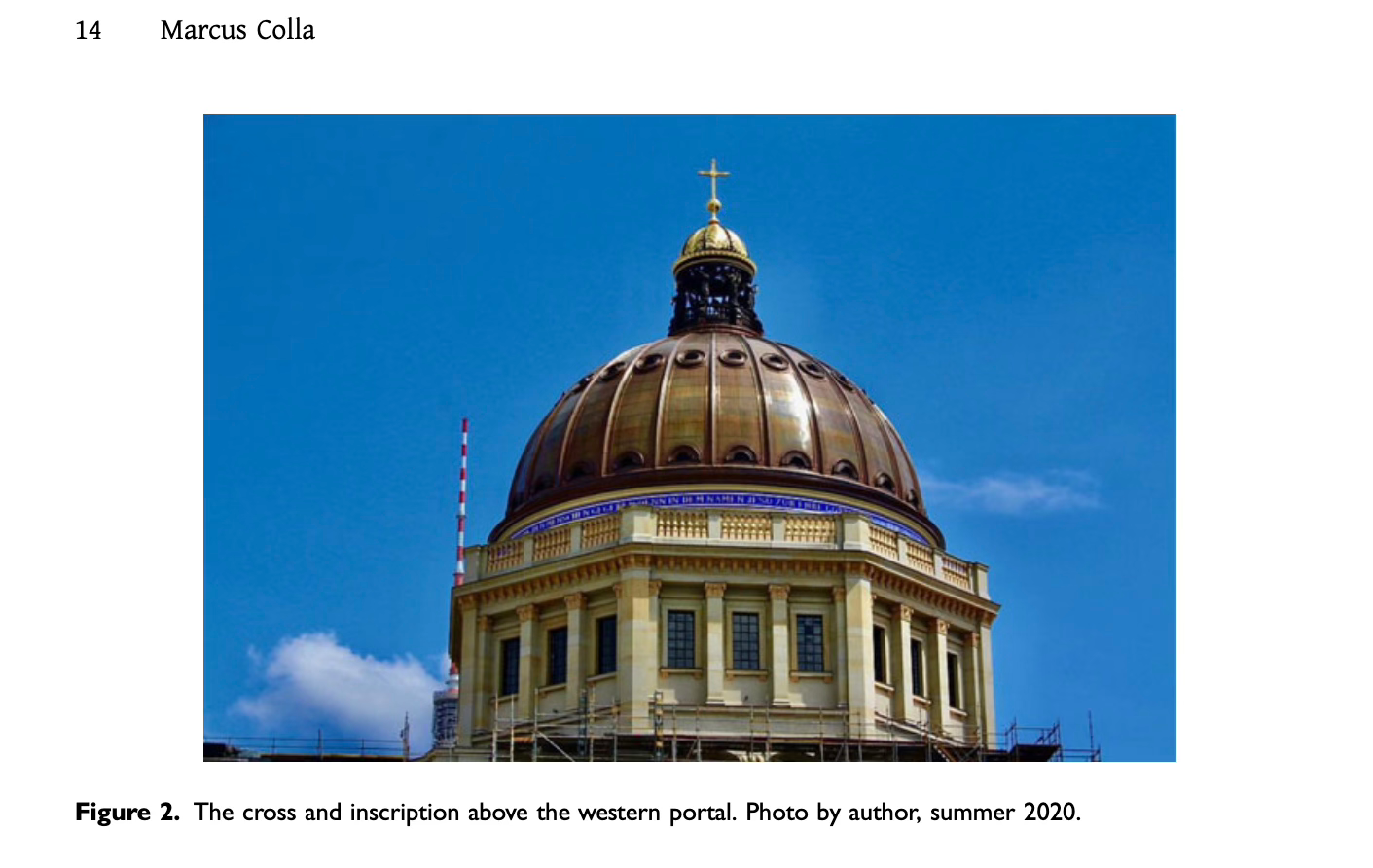

The pronouncement in May 2017 that the cross would be raised seventy meters above the Berlin skyline triggered a renewed discussion about the Prussian legacy, this time centered on the purported relationship between the reconstructed Schloss and the old Prussian state church confluence of “pulpit and bayonet.” The cross, grumbled the architectural critic Nikolaus Bernau, had initially been erected to demonstrate “the tight, profoundly anti-reformist coalition of the state church and the Hohenzollern dynasty under Friedrich Wilhelm IV.” Equally frustrating for critics was the revelation that the Schloss’ cupola would be adorned by an unsettling inscription initially composed by Friedrich Wilhelm in the 1840s: “There is no other salvation, there is no other name given to men, but the name of Jesus, in honor of the Father, that in the name of Jesus all those in heaven and on earth and under the earth should bow down on their knees”…

An inscription proclaiming “that only ‘bending your knees’ before Jesus Christ gives people ‘salvation,’” wrote Bernau in the Frankfurter Rundschau, was “unmistakably directed against the equality of Jews or indeed agnostics.” In May 2020, as the cross was finally being hoisted atop the structure, the Berlin historian and rabbi Andreas Nachama, writing in the Jüdische Allgemeine, posed the rhetorical question of whether Germany’s capital city was “actually a ‘multicolored spectrum’ (‘bunte Palette’)” and a “city of tolerance, in which Christians, Jews, Muslims, the non-religious and the anti-religious can peacefully live side by side?” “No,” he responded: “Berlin is a city which apparently continues to live with the idea that cross and Christianity alone can bring happiness.… in the year 2020 there should be no such relapse into the mental world of a Prussian king.”

There’s of course much more in the article, and I won’t reproduce it all; I’ll delimit myself to a few more lines from Marcus’ conclusions:

The Prussia that emerged from this unexpected pan-German cultural reckoning was clad in a sanitized, aesthetic form: the Prussia of Schinkel and Menzel rather than that of merciless junkers and soldier kings. Germans had apparently come a long way from the old idea that Nazism was but a racist mutation of “Prussianism.” Indeed, much of this apparent sea change in historical perception surely bore some relationship to the seismic shifts in how the Third Reich came to be understood as a historical phenomenon at much the same time: with the public focus of the Nazi legacy centering ever more on the crimes of the Holocaust, the notion that Nazism was but the last incarnation of Prussian warmongering came to seem quaintly archaic and historically unsatisfying. As a consequence, by the late 1980s, Prussia’s explosive political and cultural power had seemingly been all but defused…

Throughout the tortuous discussions about the reconstruction of the Berlin Royal Palace, Prussia remained present—even if its presence was in many cases latent rather than explicit. Whether this concerned the structure’s visual symbolism, the “enlightened” concept of the Humboldt Forum, or the defiant Preußtalgie of its right-wing supporters, the Prussian legacy was, in fact, rarely far from the surface…

Prussia is not what it used to be. Particularly outside of Germany, the name “Prussia” hardly conjures the trembling visions of goose-stepping warriors that so haunted generations past. Such is the waning force of Prussia as a historical entity in the public imagination…

Back in the early 1990s, Prussia’s “dark legend” seemed to many to have faded forever. But Prussia’s enormous influence over the course of German and European history nevertheless ensured that its legacy continued to resurface, in new ways, as a source of bitter controversy. As the debates surrounding the Humboldt Forum have revealed time and again, even those championing the sunlit uplands of a globally engaged, reunified Germany could not, in the end, outrun Prussia’s long shadow.

I’ll conclude by reproducing a picture from Marcus’ article showing that controversial cupola and inscription.

Who knows what the future of the site holds?

When I saw that public pool, I thought about how good the East German divers always were. No wonder, if everyone had access to those diving boards.

And I love the naked baby butt Lol