For those who missed out on part one, please click here:

And here continues part two of my essay.

By Way of Rabbit-Holes

The Other can be reached in two ways: by rendering him according to one’s own expectations or vice-versa. Yet, inexperience and foreign-ness can be an asset, as “the historian’s looking glass into history provides him with only a vague picture” (ibid.: 86) of the past whose present iterations are thus “refracted” (almost) without the intermediating and experiential preconceptions of the anthropologist and ethnologist. Relating two ways out – one a rekindled Historicism and the other the conscious attempt to describe the Other in his own terms while seeking to avoid, as far as this is possible, from “objectif[ying] the Other” (ibid.: 88). There being nothing new under the sun, such an “approach was already formulated by Herder” for whom “distance from the other culture, but also from one’s own” (ibid.) was the quintessential epistemological point of departure.

Cities and Reflections

Scholars, like travellers, returning to and from the field of enquiry with distinct memories: a small Konoba in the centre of the Old Town, the fishermen returning from the sea in the early morning sun, a procession of nuns quickly traversing the square in front of the cathedral.

In “the Pearl”, the travelling scholar – or tourist, for that matter – is invited into the city’s remote past and, at the same time, to examine what later generations made of this place, as well as of other cities and towns along the eastern seaboard of the Adriatic, with perhaps the Lion of St Mark being the qualitative difference. “Since the Middle Ages, economic conditions have undergone change as fundamental as the transformation of the social structures among the cit[ies’] inhabitants” (Kaser 2001: 127). As these changed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the ties between the Adriatic and the people dwelling along its shores have grown more tenuous. “Today, the sea offers a living only to a few” whose sources are the “floods of tourists” that visit “the Pearl”, augmented in more recent times by those who wish to visit some of the scenes where a popular fiction series-turned-TV show was filmed (ibid., my modifications). Whatever the proximate cause of the visit, research or leisure, the traveller may or may not disappoint the inhabitants when showering his hymnals on the postcard – social media – image of the city and prefers a fictional version to the present one, though one must be careful to use the proper “code”: paise of the ancient metropolis might easily be misunderstood for ill-advised nostalgia, enthusiasm for the fake scenery of its Americanised pop-culture image cannot compensate for a certain lost grace and sentiments of having sold out among the local populace.

Cities and Memories

Not unlike the Latin-Slav symbiosis that long characterised the communities along the Adriatic’s eastern seaboard, these old-new, fake-real dichotomies continue to characterise the present. Having turned their backs to the sea from the eighteenth century onwards, the inhabitants of the “the Pearl” and its neighbouring cities today exhibit an uneasily temporal co-existence between being overcrowded bordering on being overwhelmed by especially cruise tourists mainly interested in a very much condensed, hyper-focussed visit during the summer months – versus the empty streets, closed restaurants, and very much desolated scenery during the cold, windy winter months.

Much of this kind of tourism offers the (mainly) illusory form of individuality that comes with the artificial “mainstreaming” of “the tourist experience” by way of highlighting certain aspects that reek of historical nostalgia, fake history, and selective remembrance. All of this was reinforced by the independence of Croatia in 1991 that cemented into place “the Pearl’s” break with its maritime past. To the Western tourist, ignorant of most of his or her own past, none of this matters. Arguably, neither do the painful experiences of the “Balkan Wars” of the late twentieth century. If anything, to the stranger passing through “the Pearl” and her neighbours, the one thing he or she might note, in early August, are the fireworks that light up the night skies in celebration of “Victory Day”.

Cities and Remembrance

Whatever the merits of naming squares after long-dead patrons, such as Ivan Gundulić, long hailed as the chief protagonist of South-Slavic drama and poetry of a long by-gone era, the rebuilding of “the Pearl” after the conflicts of the 1990s exhibits some distinctly ahistorical qualities. Still, most tourists happily ignore these pitfalls of history as they are “not there to be impressed by the city’s former glory”; in fact, “quite a lot of them possibly think” they are “in some kind of Disney World, with historical scenery set up for their personal pleasure” (ibid.: 136, my modifications).

These remarks were written down almost a quarter-century ago, hence we shall add: historicity and authenticity are, factually, no necessary pre-requisite, if the ubiquitous “Game of Thrones” tour offers in Dalmatia’s cities and towns are any indication. What remains are – pleasure, and perhaps blissful ignorance of the history of “the Pearl” and the other cities along the eastern seaboard.

Cities and Boundaries

Locals go way out of their way to cater to the masses of tourists who, not unlike historically illiterate barbarians, “happily ignore all boundaries and barriers” that characterise everyday life outside the holiday season (ibid.: 137). While these qualities characterise life along the Adriatic’s eastern seaboard, they hold perhaps more true for “the Pearl” than for other, more industrial centres, such as Split and Rijeka. None of these “other places”, however, exhibit the same kind of museum-esque qualities as reconstructed Dubrovnik. If anything, “the Pearl” remains in a constant state of flux, albeit “frozen” in a state that never existed, and in this (un)happy state it will remain.

Cities and (in) History

The annals of the historical anthropology of south-eastern Europe contain many maps from various bygone eras: from pre-Roman antiquity via the arrival of the Slavic peoples and the genesis of the various principalities, kingdoms, and empires to the era of Ottoman domination and beyond.

The enquiring interlocutor asked the travelling scholar: “You, who go about exploring and who see signs, can you tell me about which of these various insights are still relevant for us?”

All of them are, in their own right and in their specific contexts; what Todorova defined as “Balkanism” may be a foreign, if not exotic, concept formed and imposed “over two centuries mainly by Western travelers”; yet, unlike, say Orientalism, “Balkanism refers to a concrete geographic entity and to Byzantine and Ottoman histories” (Kaser 2004: 227).

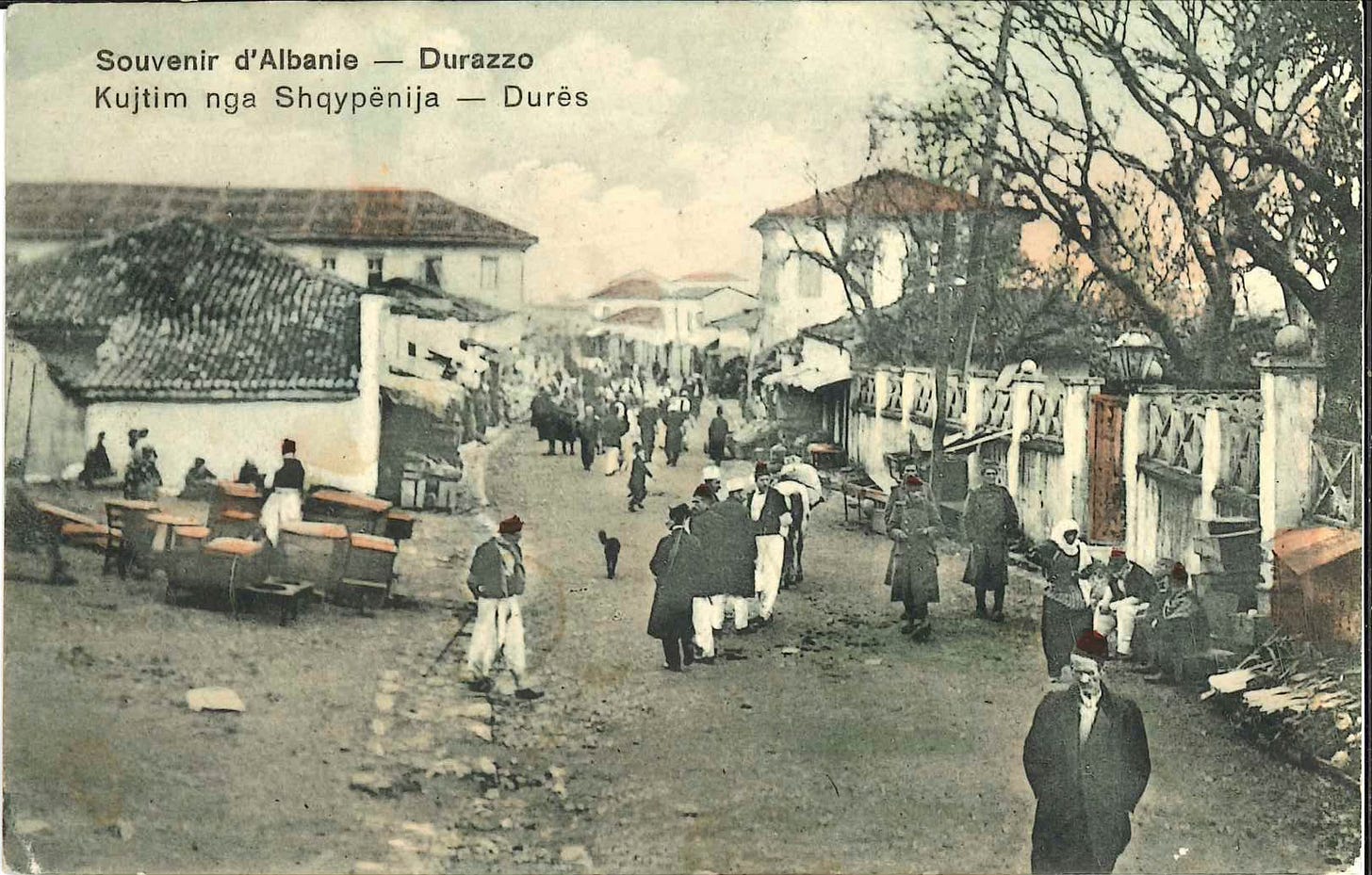

Ill. 2: Souvenir from Albania—Durazzo/ Durrës, 1913

Picture Credit: Erich Sonntag Postcard Collection, Stephan Sander-Faes

In light of the ensuing “discursive hardening”, it is quite impossible to draw a truly representative map or settle on more or less fixed dates for this event or that development. In earlier times, certain peoples and areas were “ascribed to the West”, while others, “bearing the negative imagine, became representative of the Balkans” (ibid.: 228). Eventually, these competing visions coalesced into an incongruous mental landscape that artificially divided a shared history dogmatically. Far too long, ahistorical explanations were offered to explain firmly historical facets that offered little, if any, space for differentiation or nuances. The issue, of course, “is not if [these explanations] were correct or not, but the kind of discourse they produced”. There is, in other words, little use in claiming to “‘throw the[se] publications away and let us look at the Balkans as they really were’”, for the main problem is not the realities that are described, related, in our mental landscape, but that these are “selective one[s]” (ibid.: 228, my modifications).

“The Balkans” and Scholarship

One of the core features of post-Cold War scholarship is its increasingly transnational outlook across formerly “fixed” categories. Karl Kaser’s scholarship is firmly rooted in this transformational period, which perhaps had its most profound influence over Western scholarship as restored archival access and scholarly exchange across the former ideological divide call(ed) into question many of the certainties and views held by “Westerners”.

If anything, Kaser’s influence, whether duly acknowledged via citations, critical discussion, and scholarly reviews or more implicit via the astounding rate of success in academia of his (former) Ph.D. candidates are his enduring legacy. His contribution to the study of south-eastern Europe, long “the West’s” proverbial poor relation, was equally massive and far-reaching: among the first “Westerners” to embrace the consequences of cross-cultural encounters, his inquisitive approaches fell on fertile ground, at least in certain enclaves of “the Balkans”. Undeterred, Kaser ventured boldly into the fray of long-held stereotypes, contributed to the deconstruction of many a national myth in the area – and, by implication, its “Western” counter-myths – and emphasised the necessity to do so “due to the imposition over parts of south-eastern Europe of a protectorate by the UN and NATO”, as he eloquently put it in his textbook (Kaser 2002b: 206).

The continued existence of said protectorate over Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo indicate the lasting necessity of engagement with the area. Moreover, Slovenia and Croatia have since joined the European Union and NATO, with the other countries of “the Balkans” remaining in a kind of more (NATO membership for Montenegro and – now – North Macedonia) or less integration limbo, such as Serbia.

Karl Kaser remained unbound and undeterred by fixed categories, historical or imagined. For him, the travelling scholar, “the Balkans” were an equally shape-shifting meta-phenomenon that always pointed beyond micro-macro or East-West dichotomies (dialectics): rather, we would be talking about Europe en miniature, that is, something that the seventeenth-century philosopher Leibniz called “a monad” (Peltonen 2001: 349-350, 355-356).

Cities and Remembrance (author’s note)

In this way, the influence of Karl Kaser’s scholarship on the historical anthropology of south-eastern Europe may perhaps be best paraphrased via an adaptation of Italo Calvino’s fictional dialogue between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan in The Invisible Cities:

“Every time I describe a place I am saying something about the western Balkans”. (Calvino 1974: 85-86, my modifications)

Apart from my personal exchanges with Karl Kaser over the years and the articles cited below, this essay is furthermore influenced by Italo Calvino’s The Invisible Cities.

References

Calvino, Italo (1974), The Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver. Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Kaser, Karl (2001) “Dubrovnik’s Compromise with its History: New Readings of a ‘Frozen’ Text”. Anthropological Journal on European Cultures 10, 125-141.

Kaser, Karl (2002a) “Between the Archives and the Field: The Historian in the European ‘Wilderness’”. Anthropological Journal on European Cultures 11, 73-91.

Kaser, Karl (2002b) Südosteuropäische Geschichte und Geschichtswissenschaft. 2., völlig neu bearbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage. Wien-Köln-Weimar: Böhlau.

Kaser, Karl (2004) “Peoples of the Mountains, Peoples of the Plains: Space and Ethnographic Representation”. In: Nancy Wingfield (ed.) Creating The Other. Ethnic Conflict and Nationalism in Habsburg Central Europe. New York: Berghahn, 216-230.

Peltonen, Matti (2001) “Clues, Margins, and Monads: The Micro-Macro Link in Historical Research”.History and Theory40, 347-359.

Thank you for reading.

The truth is that you cannot see the way a place or its people actually are, because you can only see them the way you expect them to be. You see others through your own experiences. They are bounded by what you consider possible or even probable. It’s human nature. We rarely escape this limitation to recognize what is actually there.

Because of this it is rare that anyone from outside of a culture ever sees it as it truly is, try as we might.

Having said that-You’ve done right by your old master.