Senj, Croatia, a Place where Pirates (Uskoks) Once Roamed

A few notes about history, geography, and literature from a bygone era

It’s the weekend, finally, and I first wish to apologise for being a bit ‘slow’ this week: I’m on a deadline for the submission of a book manuscript, which is in 10 days. While I’m quite positive about meeting the deadline, much needs to be attended to that isn’t directly related to, well, writing. These things include finalising the corrections—one of the common misperceptions about academic writing, it would seem, is that all the scholar does is to, well, write a manuscript.

Alas, doing so includes going through the references, making sure the tables and figures are done in the right way, having really good and useful maps (I like making them as many academic publications in the humanities feature really bad-to-worse such elements), and, of course, providing the Appendix. All of these latter things take their time and are, at times, quite mind-numbing but they are essential. I’m almost there, and I’m quite positive about meeting the deadline. But I do hope you, dear readers, won’t hold this against me.

A Brief History of Senj

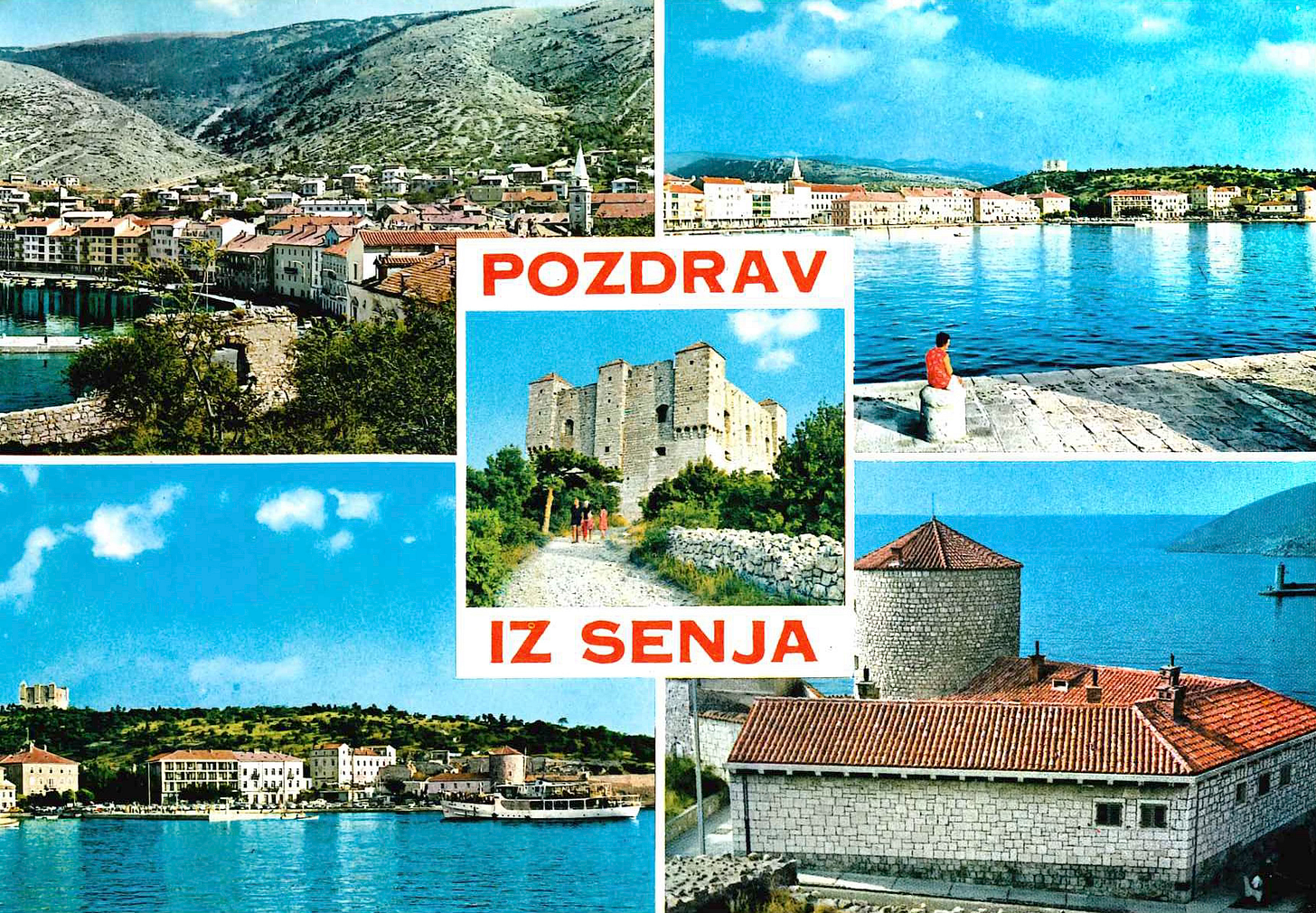

Now, enough about my week, here’s a bunch of picture postcards from beautiful Senj, Croatia, a small town with a wonderful and variegated history. From Wikipedia:

Senj is a town on the upper Adriatic coast in Croatia, in the foothills of the Mala Kapela and Velebit mountains…

The symbol of the town is the Nehaj Fortress (Croatian: Tvrđava Nehaj) which was completed in 1558. For a time this was the seat of the Uskoks (Italian: Uscocchi), who were Christian refugees from Ottoman Bosnia resettled here to protect the Habsburg borderlands. The Republic of Venice accused the Uskoks of piracy and declared war on them which led to their expulsion following a truce in 1617.

The 18th century brought some prosperity, especially with the construction of the Josephina (named after Emperor Joseph II) linking the Adriatic coast via Senj to Karlovac. The railway line built in 1873 between Fiume (Rijeka) and Karlovac did not pass by Senj which held back further development.

That might be because there’s the Dinarid mountain range ‘in-between’ the coast/Senj and the flatter, more open terrain in the hinterlands. It’s the same today, with the new motorway leading south to Split and Dubrovnik, and if you’d like to visit Senj, it takes some more driving on small mountain roads.

Until 1918, the town was part of the Austrian monarchy (Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, Lika-Krbava County after the compromise of 1867), in the Croatian Military Frontier (Regiment III).

In the fall of 1943, during World War II, when Fascist Italy capitulated, the Partisans took control of Senj and used it as a supply port. Subsequently, the Luftwaffe started bombarding the town. By the end of the year they had demolished over half of the buildings in town and inflicted heavy civilian casualties.

If, at this point, you’re interested in learning more, I would recommend the following title by Catherine Bracewell, The Uskoks of Senj: Piracy, Banditry, and Holy War in the 16th-Century Adriatic (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992).

Greetings from Senj

The castle—Nehaj fortress—in the middle once belonged to the Uskoks of Senj, widely-feared 16th- and 17th-century corsairs.

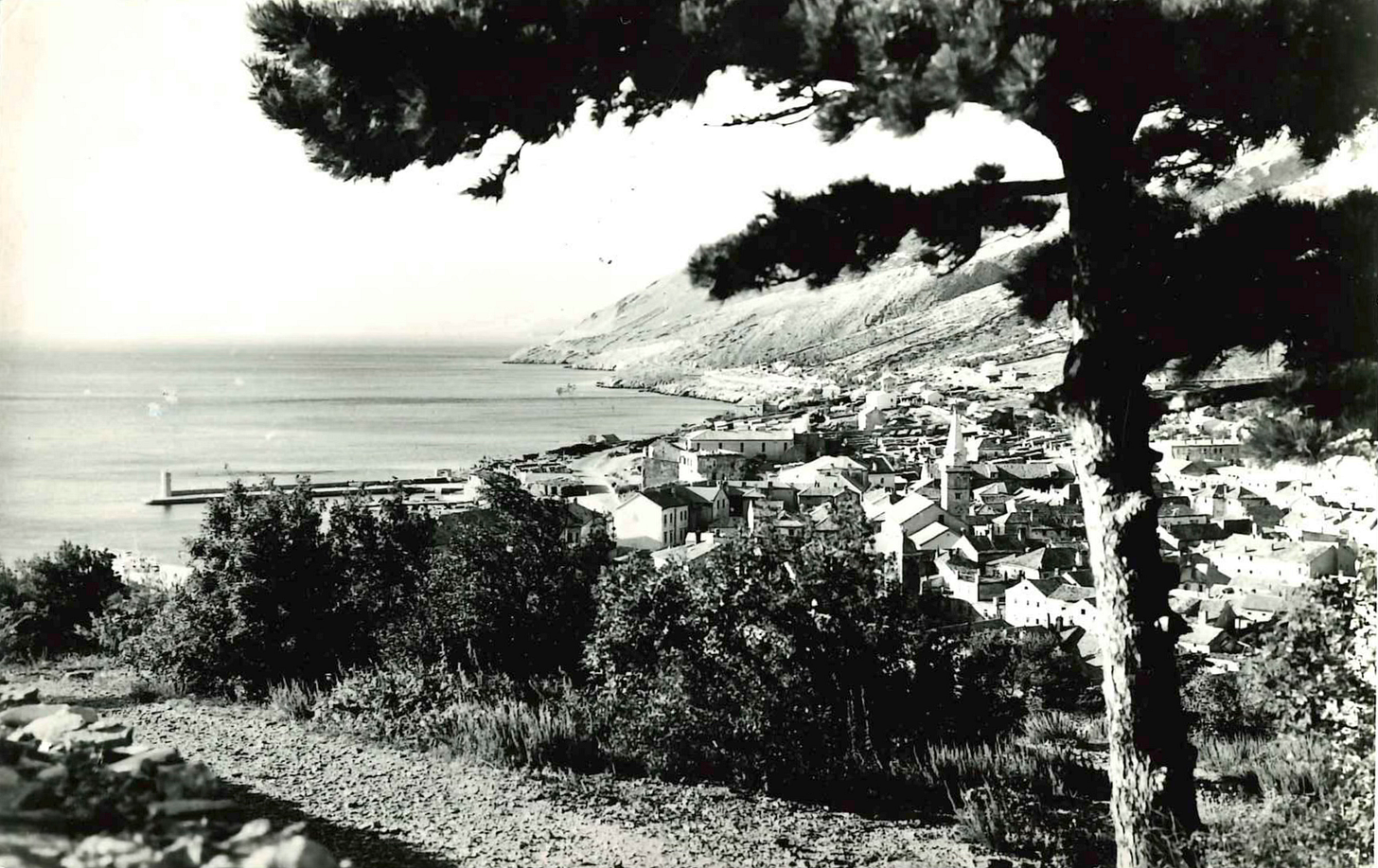

Below, another picture of the place, predating the Second World War.

The Outsiders of Uskoken Castle

Another thing about Senj is the youth novel, The Outsiders of Uskoken Castle (trans. 1967), written by exiled Kurt Kläber in 1941 (which we’re reading with my daughters these days, hence the inspiration); the original title was Die rote Zora und ihre Bande.

Here’s a bit from Wikipedia about the novel:

The story is about the adventures of Zora and a band of children who live in the ruins of an Uskok castle on the coast of Croatia. The children steal out of necessity, because they have no parents or other family to look after them. They are frequently involved in conflicts with the town's residents and reject the authority of adults, except for Gorian, an old fisherman who helps the children. When he needs help the children repay his kindness by coming to his rescue.

Background of the Story

Kläber traveled to Yugoslavia in 1940, where he met Branko, Zora and her gang. The book is based on his experiences with these orphaned children in the Croatian city of Senj, where there is a castle called Nehaj Fortress.

In real life as in the story, the first child Kläber met in Senj was Branko, a boy who had recently been orphaned. Zora told Branko that the police were investigating him for stealing food. So Kläber was introduced to Zora. He wanted to take Branko and Zora back to Switzerland with him, but his refugee status made that impossible. Instead he wrote the children’s story, intending to make it a political tool to draw attention to marginalized people in Europe. Zora became the central figure because Kläber was impressed with the way she organized the children into a gang and taught them solidarity. The boys accepted her as their leader.

One of the core features of the book is—it’s still printed, and it’s one the more interesting novels about the 20th century.

As you may have gathered, it was written by an exiled German Communist, Kurt Held, who left Hitler’s Germany and was initially granted asylum in Switzerland, and his life’s story is told by, incidentally, none other than the Berlin-based Der Tagesspiegel a few years ago on the occasion of his youth novel having been made into a movie:

Class Struggle in the Classroom

Kurt Kläber was a revolutionary poet until he fled from the Nazis. In exile, he continued to write about justice. His most famous book is from 1941—now [that article is from 2008] it has been made into a cinema film: ‘Die rote Zora’…

Kurt Kläber, German revolutionary writer and left-wing cultural functionary, wrote it in exile in Switzerland, although he did not have a work permit. It was an experiment. Would he manage to write a book for young people? Would it succeed? In the books before and after, the poor were among themselves.

Before that, in 1928, he had a hunchback on a boat journey from New York to Rotterdam say: ‘We proles are cows, and we are milked in every country.’ A Belgian shouts: ‘They treat us worse than cattle!’ And a Dane replies: ‘They treat us like labourers.’ It's all about the foul-smelling fish they are served and the cold in the cabins. It is the novel ‘Passengers III Class’ [orig. Passagiere Der 3. Klasse, 1927].

After that, in 1941, he sent a ragtag gang of children to help the old fisherman Gorian, who has to hold his own against the big companies.

‘The fishing grounds are yours, aren’t they?’, a boy asks the old man.

‘Yes, they are. But only as long as we’re free and haven’t sold ourselves to the companies. If we work for them, we have to give them our fishing grounds, and then we’ve not only sold ourselves to them, but also our fish.’

He wrote this story under a pseudonym. He called himself Kurt Held. The book was called ‘Die rote Zora und ihre Bande’ (The Red Zora and her gang) - it became a worldwide success: millions of children were carried away by the intrepid gang leader and her cheeky, brave, loyal friends, who live in a dilapidated castle and steal out of necessity. They are chased through the gardens by the rich villagers and their cowardly grammar school sons, put in gaol and yet freed again. It is a book that awakens the desire for adventure and friendship. It has been translated into 18 languages and is still being reprinted today, now in its 37th edition in Germany...

Kläber did not want to write down what he made up. How could he have used it to criticise capital?

Kläber—born in Jena in 1897, father: a foreman at the Zeiss company, mother: housewife—has seen and experienced a lot in his life. He refused to go to secondary school, failed as an apprentice locksmith, joined the Wandervögel [an itinerant, Neo-Luddite youth movement against industrialisation] and Guttemplern, served in the First World War and returned home sick, joined several youth movements, wrote poetry, travelled America, tried his hand as a miner, organised events for the KPD, co-founded the ‘Bund proletarisch-revolutionärer Schriftsteller’ [Assoc. of Proletarian-Revolutionary Writers] and ran the associated magazine ‘Die Linkskurve’ [lit. ‘Left Bend’]. Then the Roaring Twenties came to an end, some people continued to cry for the Kaiser, others for Karl Liebknecht, Stalin rose in Moscow and Kläber’s enthusiasm for class struggle died out.

His Dane in ‘Passengers III Class’ says: ‘It’s strange about socialism, the closer it gets to realisation, the more it loses its colour.’

The most interesting aspect of Kläber/Held’s life as a communist was—that once he saw its tyrannical visage, he lost faith. This is actually why, I think, his novel about a bunch of kids in a place few people will have ever heard about still resonates. Here’s the final paragraphs from the piece in Der Tagesspiegel, which relates where, when (in 1940), and how Kläber/Held found the inspiration for this novel:

The couple travelled as often as they could. Once [in 1940] they travelled to Yugoslavia, where they collected royalties for licensed editions of [Held’s wife] Lisa Tetzner’s children's books. More by chance than anything else—Kurt Kläber wasn't feeling well—they broke off their journey in the Croatian coastal town of Senj.

It is a humid day. They take their luggage to the hotel on the market square and walk through the town. Kurt Kläber spots a skinny boy and suddenly says: ‘That boy there, that's the one.’

He calls him over and invites him to dinner. The boy's friends come over. Among them is a girl with flaming red hair. ‘Zora La Rouquine,’ explains the waiter. The police are always after her, but they never catch her. In the afternoon, Kläber climbs with the children to her hiding place in an abandoned castle above the city— and a few months later the book is finished.

The book is about justice and solidarity, the good guys are always brave characters, the bad guys bat-eared, hunchbacked, bald-headed, and sweaty. Capital is ugly, that hadn’t changed. Lisa Tetzner announced the book to her publisher Sauerländer: The children, she wrote, would learn about the concepts of good and evil, theft, possession and property in the course of the plot and through the intervention of understanding adults, would be imperceptibly incorporated into a labour process and feel happy in it. Kläber sees no solution in being an outsider. He had experienced this too painfully himself. ‘I was probably always on the edge’, he writes about himself: he didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, didn’t sit in pubs, didn’t play cards [and, obviously, didn’t go along with the majority of communists who happily acceded to celebrating Stalin, some even did so after 1956] .

Not everyone liked the social criticism in Kläber’s children's books, and the Sauerländer publishing family was criticised for publishing communists. Kläber reacted angrily to such criticism. Helping the poor doesn’t make you a communist, it makes you a human being. ‘I praise my village neighbours and the ordinary people here who, despite all the spiteful whispers, unanimously elected me as their citizen and still stand by this election today and only laugh at all the other voices and whisperers’, he wrote to Sauerländer. He was one of the most hated people behind the Iron Curtain, but: ‘I bear this hatred with pride.’

Kläber died in 1959.

Since Christmas is coming up and lack a good present, you might wish to enquire about The Outsiders of Uskoken Castle. Perhaps because of the author’s, well, let’s say ambiguous relationship with Socialism/Communism, it might be worth your time.

For those who read German, here’s an interesting website with lots of information about the original places in and around Senj where the novel is set.

Finally, another postcard, which I found among the ones labelled “Senj”, but I’m unsure if it’s ‘there’ (still). It looks like from Socialist Yugoslavia.

Thank you for the book/gift recommendation.