Vienna, Spring 1945

As the guns fell silent, most Central European cities had turned to barely recognisable heaps of rubble, which renders their renaissance thereafter a feat of endurance and persistence

As I was going through the postcard boxes earlier this week, I came across a set of specimens from Vienna that caught my eye: tucked away in an envelope, there were ‘24 Images from War-Torn Vienna’, of which I am reproducing a selection here.

Much like my hometown back in 1945, these aren’t really picture postcards (although the format is quite comparable), and they’re also printed on very thin and cheap paper. Wikipedia’s ‘History of Vienna’ provides the barest of minimums of context here:

The U.S. bombings of 1944 and 1945 and the vicious fighting during the subsequent conquest of Vienna by Soviet troops in April 1945 caused much destruction within the city. However, some historic buildings survived the bombardment; many more were reconstructed after the war.

Here’s a bit more from the above-linked ‘Vienna Offensive’ article:

After arriving in the Vienna area, the armies of the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front surrounded, besieged, and attacked the city. Involved in this action were the Soviet 4th Guards Army, the Soviet 6th Guards Tank Army, the Soviet 9th Guards Army, and the Soviet 46th Army. The “O-5 Resistance Group,” Austrians led by Carl Szokoll, wanting to spare Vienna destruction, actively attempted to sabotage the German defenses and to aid the entry of the Red Army…

The battle for the Austrian capital was characterized in some cases by fierce urban combat, but there were also parts of the city the Soviets advanced into with little opposition.

The Red Army arrived in early April, and by the middle of that month, it was over, with Soviet troops pushing further westward.

Some of Vienna’s finest buildings lay in ruins after the battle. There was no water, electricity, or gas — and bands of people, both foreigners and Austrians, plundered and assaulted the helpless residents in the absence of a police force. While the Soviet assault forces generally behaved well, the second wave of Soviet troops to arrive in the city were reportedly badly undisciplined. A large number of lootings and cases of rape took place in a several-week long violence that has been compared to the worst aspects of the Thirty Years War.[16]

So much for the background and context, and now for more images from that picture series.

Spring and Summer in Vienna, 1945

We’ll start in the city centre, specifically the Parliament Building, which looked liked this once the guns had fallen silent:

During the war, the Vienna parliament building was heavily damaged by bombs. On 7 February 1945, two of the 24 monolithic columns of the central hall, made of a red-grey limestone of the Rot-Grau-Schnöll type from Adnet (Salzburg), were destroyed. The two destroyed columns were replaced in 1950 by two new ones quarried from the same quarry.[26] The two replaced columns stand next to each other and are recognisable due to the brownish colour of the marble, the lack of white marbling and slightly altered foundations. The south wing of the manor house was also badly damaged and the plenary hall of the manor house was almost completely destroyed.

Reconstruction and restoration took place between 1945 and 1956 according to plans by the Austrian architects Max Fellerer and Eugen Wörle[25].

These paragraphs are from the German version of the English Wikipedia entry linked above (and I’ve reversed their order to make the flow make more sense).

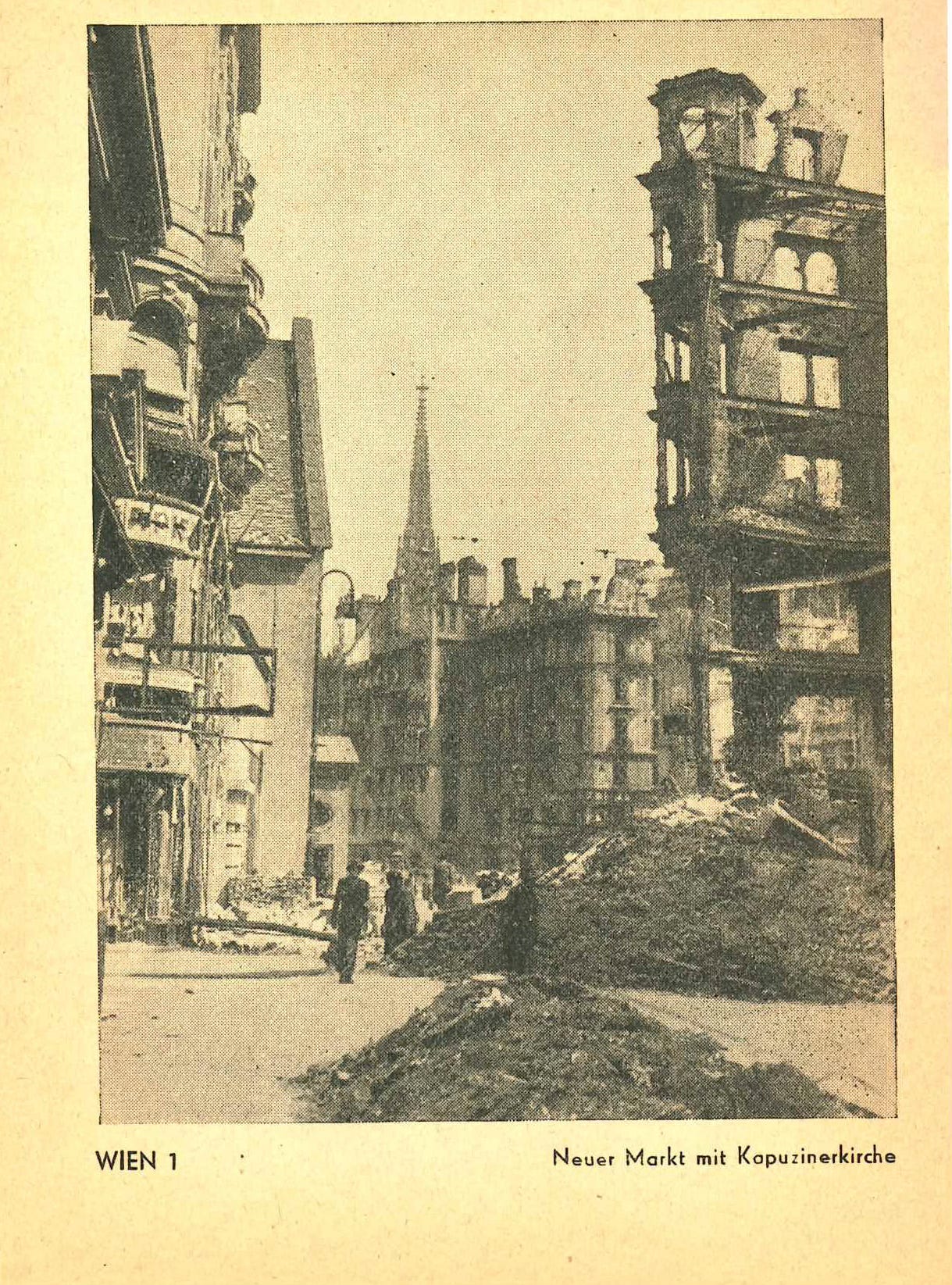

Above, an image showing the ‘New Market [Square]’ in downtown Vienna with the Capuchin Church (on the left-hand side).

When the High Market [orig. Hoher Markt] was no longer sufficient to supply the Viennese population in the Middle Ages, the New Market was created, which was first mentioned as nuiwe market or novum forum in 1234. As flour and grain were also traded here until the 19th century, the square was unofficially known as Mehlmarkt (flour market), a name that stuck until the 20th century. The square was severely damaged during the Second World War and a number of buildings disappeared and were replaced by modern structures.

In the background of the above image, Vienna’s St Stephen’s Cathedral is seen—and here’s a close-up of the war damage sustained:

With its origins dating back to the mid-twelfth century, St Stephen’s is the cathedral church of the archdiocese of Vienna and one of the city’s iconic landmarks.

During World War II, the cathedral was saved from intentional destruction at the hands of retreating German forces when Wehrmacht Captain Gerhard Klinkicht disregarded orders from the city commandant, “Sepp” Dietrich, to “fire a hundred shells and reduce it to rubble”.[4] On 12 April 1945, civilian looters lit fires in nearby shops as Soviet Army troops entered the city. The winds carried the fire to the cathedral, where it severely damaged the roof, causing it to collapse. Fortunately, protective brick shells built around the pulpit, Frederick III's tomb, and other treasures, minimized damage to the most valuable artworks. However, the Rollinger choir stalls, carved in 1487, could not be saved. Reconstruction began immediately after the war, with a limited reopening 12 December 1948 and a full reopening 23 April 1952.

Like so many parts of Vienna, the Albertina art collection similarly did not escape war damage—in March 1945, it was heavily damaged by USAAF attacks—as shown below:

Needless to say, Vienna’s infrastructure also sustained massive damages, in particular the bridges across the Danube and the Donaukanal, a side-arm that runs by the city centre. Shown below is the Franzensbrücke, or Francis’ Bridge, one of several bridges connecting Vienna’s city centre with the Second District across the Donaukanal:

During the Battle of Vienna in April 1945, the bridge was blown up by German units, and Soviet pioneers erected a temporary wooden crossing in the summer of 1945.

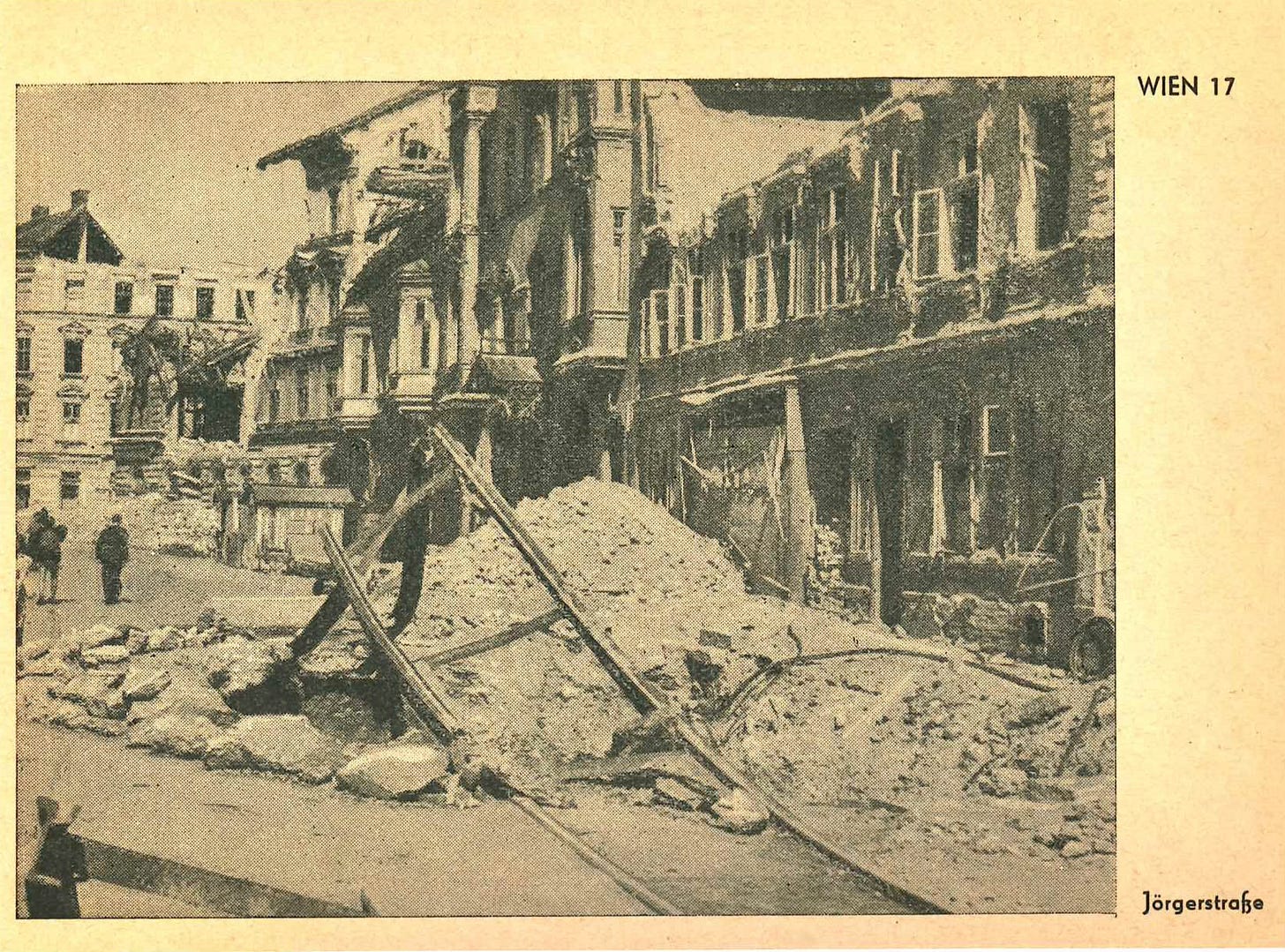

Finally, mention shall be made of the Jörgerstraße, one of the main thoroughfares of Vienna’s Seventeenth District, Hernals.

The Second World War ended in Hernals with the invasion of the Red Army on 7 April 1945. Soviet soldiers remained in Hernals until the end of August 1945, when they were replaced by American occupation troops on 1 September 1945. In addition to rebuilding the destroyed houses, the main focus was on building new flats.

Thus concludes, for the time being, our trek across war-torn Vienna, which was immortalised in Carol Reed’s 1949 classic movie The Third Man. From that article:

Six weeks of principal photography were shot on location in Vienna, ending on 11 December 1948.[18]Some use was made of the Sievering Studios facilities in the city.[19] Production then moved to Worton Hall Studios in Isleworth[20] and Shepperton Studios in Surrey and was completed in March 1949.[21]

From its German version, there is also this to learn:

Filming took place at the Vienna Central Cemetery, in the Vienna sewerage system and at various locations in the 1st district, the inner city. These include the Palais Pallavicini (Limes’ residence) on Josefsplatz, the historic square Am Hof and the Hohe Markt. Other locations include the Judengasse, the Mölker Bastei, the churches of Maria am Gestade and St Ruprecht and the Reichsbrücke bridge over the Danube.

The scenes in the amusement park of the Vienna Prater, in what was then the Soviet sector of the city, were shot at the original location - with the exception of the interior shots in the Ferris wheel carriage. The Giant Ferris Wheel [orig. Riesenrad] was reopened in 1947 after restoration work[3].

Glimpses of war-torn Vienna may be seen in the movie’s trailer, which I’ll add here to wrap up this posting:

What happened to Captain Gerhard Klinkicht? Was he Roman Catholic or just a man who did not want to see senseless destruction? This would have been a very dangerous order to disobey.

Wow. Armies in flight can be a destructive force.

What’s always amazed me is that so many of the old buildings survived. Many destroyed, but many left standing