Vintage Postcards Examined by a Linguist

A guest post by Aneta Pavlenko, courtesy of a fellow postcard afficionado

Dear readers,

serendipity striketh once more: just as I was resigning myself to a week of limited posting, my friend Aneta Pavlenko—a linguist and fellow academic with comparable interests in picture postcards—sent me a guest post we talked about some time ago.

Dr. Aneta Pavlenko is a Professor of Applied Linguistics operating, mostly, out of the United States. Please find her website here, and if you wish to go down some other rabbit-hole, I highly recommend her 2003 essay “The privilege of writing as an immigrant woman”, which explains, apart from being a very interesting autobiography, why “Eastern Europe”, widely understood, is such a complicated place (it if, it fact, is but one place).

One last note about serendipity: Aneta reached out to me after a mutual friend told her about this little weblog: the number of people interested in vintage postcards is actually higher than it would seem…

I won’t get into further details now, but I do note that I am delighted to have Aneta’s short essay appear here, and I hope you will enjoy it as much as I do.

I have lightly edited the essay (mainly for reasons that have to do with the hyperlinked content); if not noted otherwise, all pictures were provided by Aneta Pavlenko.

“Der goils shtick to me chust like glue”: Vintage postcards examined by a linguist

A guest essay by Aneta Pavlenko

Thank you so much, Stephan, for inviting me to contribute a guest post to the blog I got hooked on. I am a linguist and a big aficionado of vintage postcards, always on the lookout for these humble historic mementos on-line, in secondhand bookshops, at flea markets and antique fairs, and, of course, at postcard shows, where dealers and collectors sell cards, photos, posters, and other paper ephemera.

Picture 1. Postcard show in York, PA, 2021.

My primary interest is in the cards that reflect language practices and attitudes in the multilingual empires—Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian. The Austro-Hungarian empire also happens to be the place, where the first correspondence card was issued in 1869, according to Karin Almasy (2019). The success was unprecedented: in the first three months, nearly three million postcards were sold and other countries quickly followed suit. The craze for the new medium reached its apogee during the so-called Golden Age of Postcards (circa 1895-1915), when billions of colorful images were printed, imported, sold, mailed, and lovingly tucked into collectors’ albums all around the world. Finding imperial postcards is not easy, at least not in the USA. Fortunately, at trade shows, card collections are typically arranged by subject and my first trip around the room is to see what’s on offer under the headings ‘imperial Russia’, ‘Austro-Hungarian empire’ and ‘Turkey’. The second round is dedicated to the activity known as ‘the treasure hunt’, where collectors eagerly comb through the 25 cent boxes of unsorted postcards, a thrilling mini archaeology of sorts.

Picture 2. Treasure hunt at the postcard show in Titusville, NJ, 2024.

The cards in my collection can be divided into five categories. The first, and arguably the rarest, are images with language slogans that typically promote some form of political and linguistic nationalism. One such card comes from Prague. Printed in the early 20th century, most likely by a school association, it was part of a massive campaign that relied on posters, leaflets, postcards, circulars, and lectures to convince Czech parents in Bohemia and Moravia to renounce German schools and send their children to schools with Czech as the language of instruction (see Zvánovec, M. (2020) “The Battle over National Schooling in Bohemia and the Czech and German National School Associations: A Comparison (1880-1914)”, Austrian History Yearbook, 51, 173-192).

Picture 3. “Czech children belong in Czech schools”. Postcard printed in Prague before 1907.

Another example of ideological messaging is a postcard issued in 1939 in the Third Reich that declares “Danzig is German”. At the time, Danzig (modern Gdańsk) was a predominantly German-speaking city, surrounded by overwhelmingly Polish rural areas. Separated from Germany by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, it was declared a free city-state, to which Poland was given special rights. The loss hurt German national pride and in 1938 Germany unrolled a media campaign demanding the return of Danzig. The card asserting the city’s German identity was part of this campaign that culminated with the incorporation of Danzig into Germany on September 1, 1939, the first day of World War II.

Picture 4. “Danzig is German.” Postcard printed in Germany circa 1939.

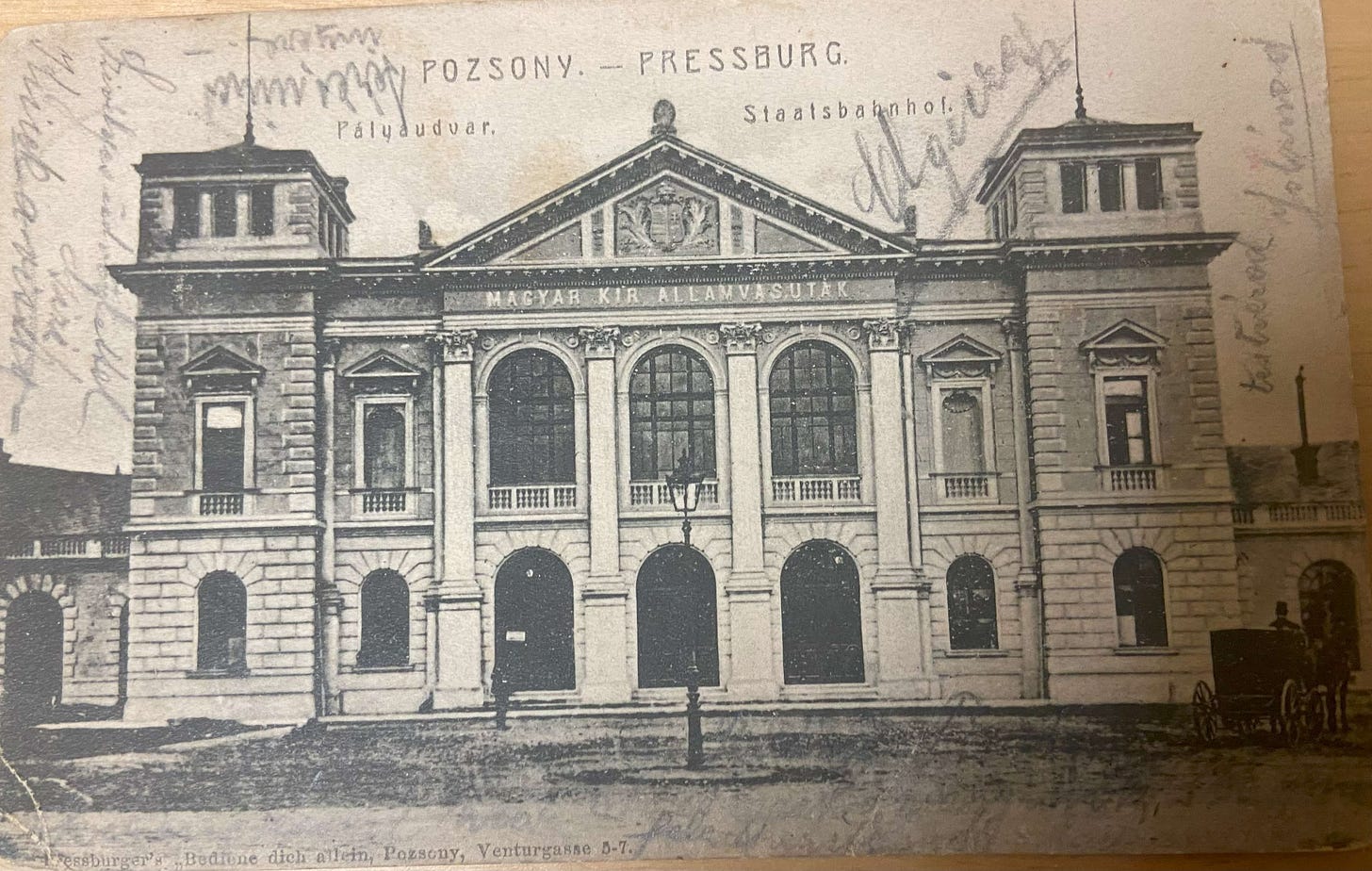

Not all ideological messages, however, are that direct. Many commercial publishers conveyed their ideas about linguistic and national identities of their cities, regions and countries – and presumed preferences of the postcard consumers – through language choices on captions. Take, for instance, the city in the Kingdom of Hungary known as Pozsony in Hungarian and Pressburg in German. In the early 20th century views, captions usually appear in Hungarian, the state language, and German, the imperial lingua franca. Missing in action is the name Prešporok in Slovak, the mother tongue of 15% of the city’s population in 1910. Following World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the city was renamed Bratislava (1919) and assigned to the newly formed Czechoslovakia. New postcards sent greetings from Bratislava, Pozsony and Pressburg but, as time went by, German and Hungarian street signs and captions disappeared from the public view.

Picture 5. Train station in Pozsony-Pressburg. Postcard mailed in Hungary in 1906.

Note also that the sign for Hungarian Railways appears in Hungarian only, consistent with an aggressive Magyarization campaign conducted in the period before World War I. Other countries and cities were more laissez-faire, as seen in postcards that preserve street and shop signs, known collectively as linguistic landscapes. Below we see one such postcard from a Chinese city of Harbin. Founded in 1898 as a stop on the Russian-built Chinese Eastern Railway and planned by Russian and European architects, early 20th century Harbin was effectively a Russian colony and, in the wake of the 1917 Russian revolution, became home to one of the largest émigré diasporas in the world. Postcards of Russian Harbin with its Cyrillic signage were fondly preserved by its former residents as a memento of a treasured past.

Picture 6. Harbin. Kitayskaya (Chinese!) street, with Russian-language signs for a bookstore, a pharmacy, and a restaurant. Printed in Moscow before 1917.

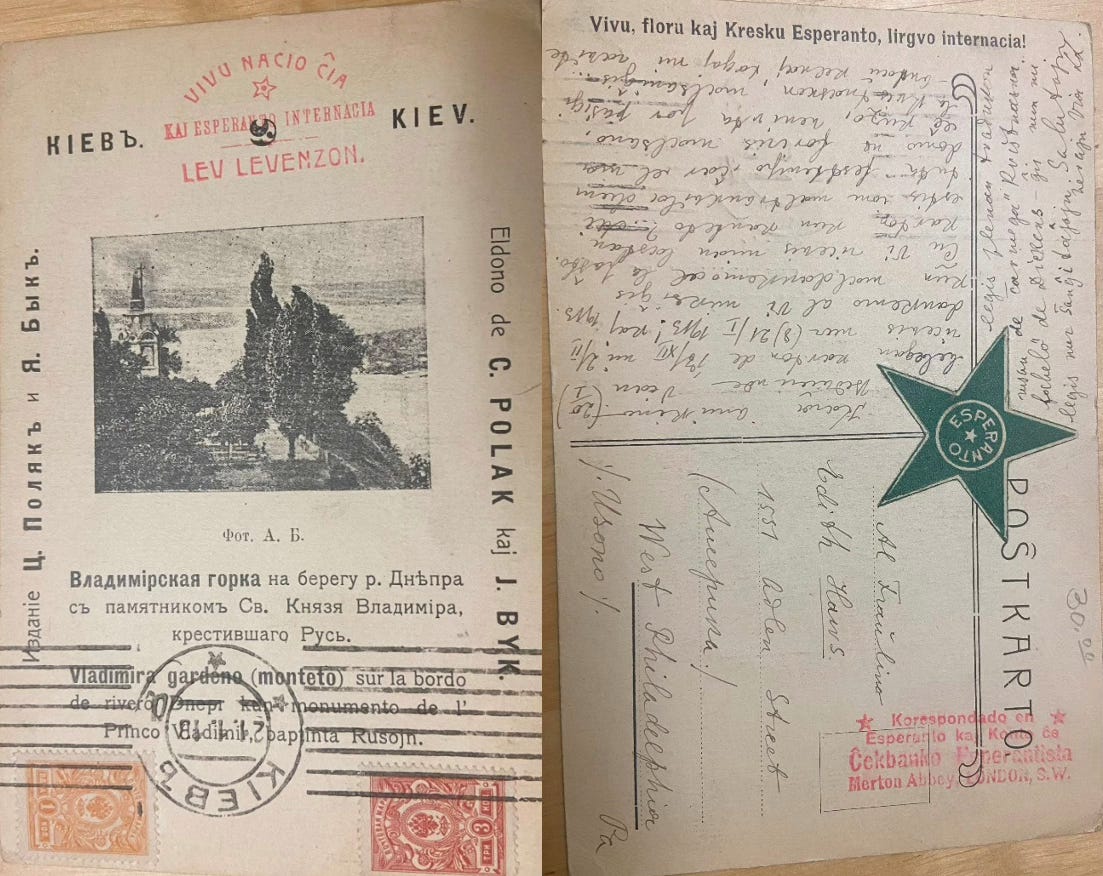

Immigrant societies also printed postcards in what we now call ‘minority languages’. My collection includes several such cards but my personal favorite is a postcard in a language created to overcome national and ethnic divisions—Esperanto. In 1913, it was mailed from my native city, Kiev, to my adoptive city, Philadelphia. When I found the card in 2021 (at the show in picture 1!), I did some research with the help of a wonderful Esperantist colleague H.T. and learned that the sender, Lev Levenzon, was a well-known poet and writer, whose writings are preserved in both Russian and Esperanto. Head of the Kiev Esperanto society, Verda Stelo [Green Star], in 1913 he manned a kiosk at the all-Russian exhibition in Kiev, where attendees could purchase self-study Esperanto manuals. His addressee Edith Haws was a member of the corresponding society in Philadelphia and the message, as you would expect, was written in Esperanto. Card captions are in Russian and Esperanto and the address is in English with an added Russian word, America. Levenzon’s card highlights another aspect of vintage postcards worth paying attention to—multilingual messages. While many cards are inscribed in a single and fairly standard idiom, here and there you find senders inserting foreign words, writing in a second language or a lingua franca, or playfully mixing multiple tongues.

Picture 7. Monument to St Vladimir in Kiev. Postcard printed in Kiev, 1913.

Publishers also engaged in language play: in the UK some images were captioned in mock Welsh and in the USA cards making fun of foreign accents ranged from fairly offensive to quaint, like this charming early 20th century postcard from a series known as “Dutch kids”.

Picture 8. “The girls stick to me just like glue when they have got their skates on.” Postcard printed in the USA, mailed in 1906.

There are, of course, many more linguistic curiosities to discuss but what I love about the postcards above are the glimpses of changes in language attitudes that accompanied the key historic processes of the 20th century: the rise of nationalism, migration, the failed attempt to unite the world through Esperanto and the unraveling of the multilingual empires replaced by nation-states founded on the principle of one nation = one language.

Aneta thank you, fascinating reading and you’ve open up a whole other angle on “postcards” for me.

And great timing as only a short while ago I asked about the origin of postcards and you perfectly gave me answers right at the start of your article.

Very enjoyable. Thank you