Visit the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition

Today, we'll check out the foreign contributions, visit more of the pavilions of the once-mighty French Empire, and consider what remains to this day of the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition

If you missed the first part, please venture over here:

For today’s posting, more context is appropriate (via Wikipedia; references omitted):

Politically, France hoped the exposition would paint its colonial empire in a beneficial light, showing the mutual exchange of cultures and the benefit of France's efforts overseas. This would thus negate German criticisms that France was “the exploiter of colonial societies [and] the agent of miscegenation and decadence”. The exposition highlighted the endemic cultures of the colonies and downplayed French efforts to spread its own language and culture abroad, thus advancing the notion that France was associating with colonised societies, not assimilating them.

The Colonial Exposition provided a forum for the discussion of colonialism in general and of French colonies specifically. French authorities published over 3,000 reports during the six-month period and held over 100 congresses. The exposition served as a vehicle for colonial writers to publicise their works, and it created a market in Paris for various ethnic cuisines, particularly North African and Vietnamese. Filmmakers chose French colonies as the subjects of their works. The Permanent Colonial Museum (today the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l’immigration) opened at the end of the exposition. The colonial service experienced a boost in applications.

26 territories of the empire participated in the Colonial Exposition Issue of postage stamps issued in conjunction with the Exposition.

As an aside, I don’t know if any of you, dear readers, noticed—but few, if any, of the reverse sides of the vintage postcards in Erich Sonntag’s collection have stamps (left). As I learned from my aunt, my grandfather carefully removed them and donated them to charity.

The booklet in question here, though, contains 24 postcards, none of which were ever mailed (and I think Erich Sonntag acquired the booklet “somehow”).

With that being said, let’s have a look at more vintage postcards, shall we?

The Foreign Pavilions

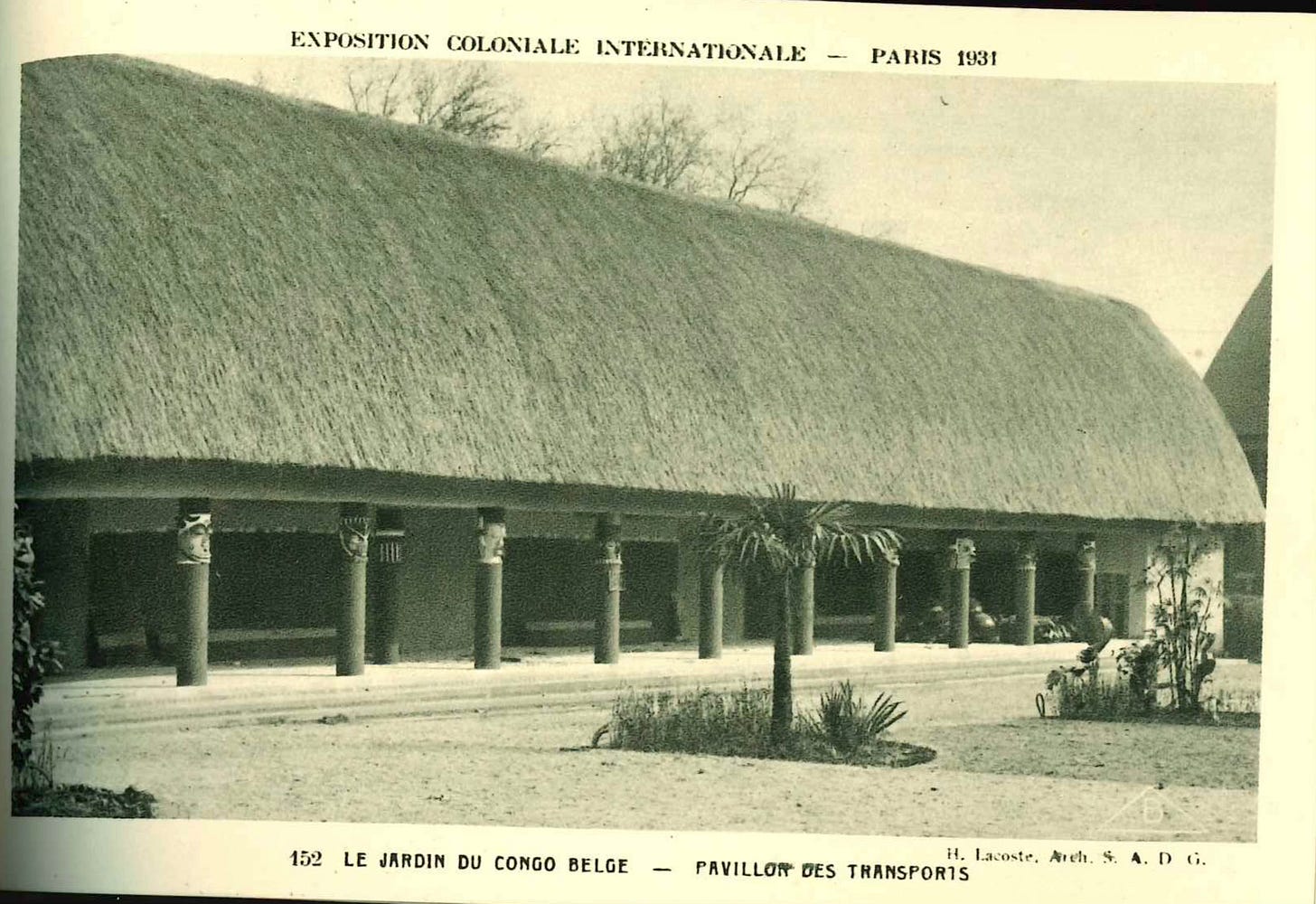

First up, the Belgian contribution, which focussed on the Congo, the inspiration for Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and the quoted information in the below section is from the French Wikipedia entry (as the English entry is quite devoid of such details):

The Belgian Congo Section covers an area of 2 hectares, with more than 10,000 m2 of buildings around a vast courtyard [this is shown on the above postcard], preceded by a monumental gateway:

In the centre, there was the Pavilion of Honour, topped by a thatched roof and 3 domes, houses all the information on the Belgian Congo [this is the “dome” visible in the background];

On each sides, there were ancillary pavilions showcasing metropolitan and exotic industries.

Below, another view of the above portico from across the courtyard:

Moving on, we visit the Italian Pavilion, consisting of the following parts:

The Kingdom of Italy pavilion features the following group of monuments:

The main pavilion, a reproduction of the Basilica of Leptis Magna in Libya [this is shown below], a Roman monument dating from the first century, presenting the Italian colonies of Italian Somalia, Eritrea and Libya;

Then there was the Rhodes pavilion, in mediaeval style and adorned with seven towers, dedicated to the history of the island.

There were furthermore a monumental fountain, surrounded by two African marabouts, and Bedouin nomad tents, and a a restaurant.

Samboucs (Somali boats) sailed on the lake.

Lest we all get to excited about these foreign contributors showcasing, arguably, many of the worst offenders of European colonialism, one should not overlook that these sentiments, while not entirely absent from the exhibition (more about this below), there were no significant doubts in the United States about participation, and this is what the US-American pavilion looked like:

You saw this correctly—a replica of George Washington’s Mount Vernon:

The United States section is arranged around a reproduction of G. Washington's house in Mount Vernon, built in 1743. The reproduction is faithful, both inside and out.

Two small houses linked by covered galleries are located on either side of the house: these are the kitchen and Washington’s office, where an exhibition on the Territory of Alaska is on display.

Other buildings in the same style complete the complex, presenting exhibits from the United States government and foreign territories (Caribbean and Pacific islands).

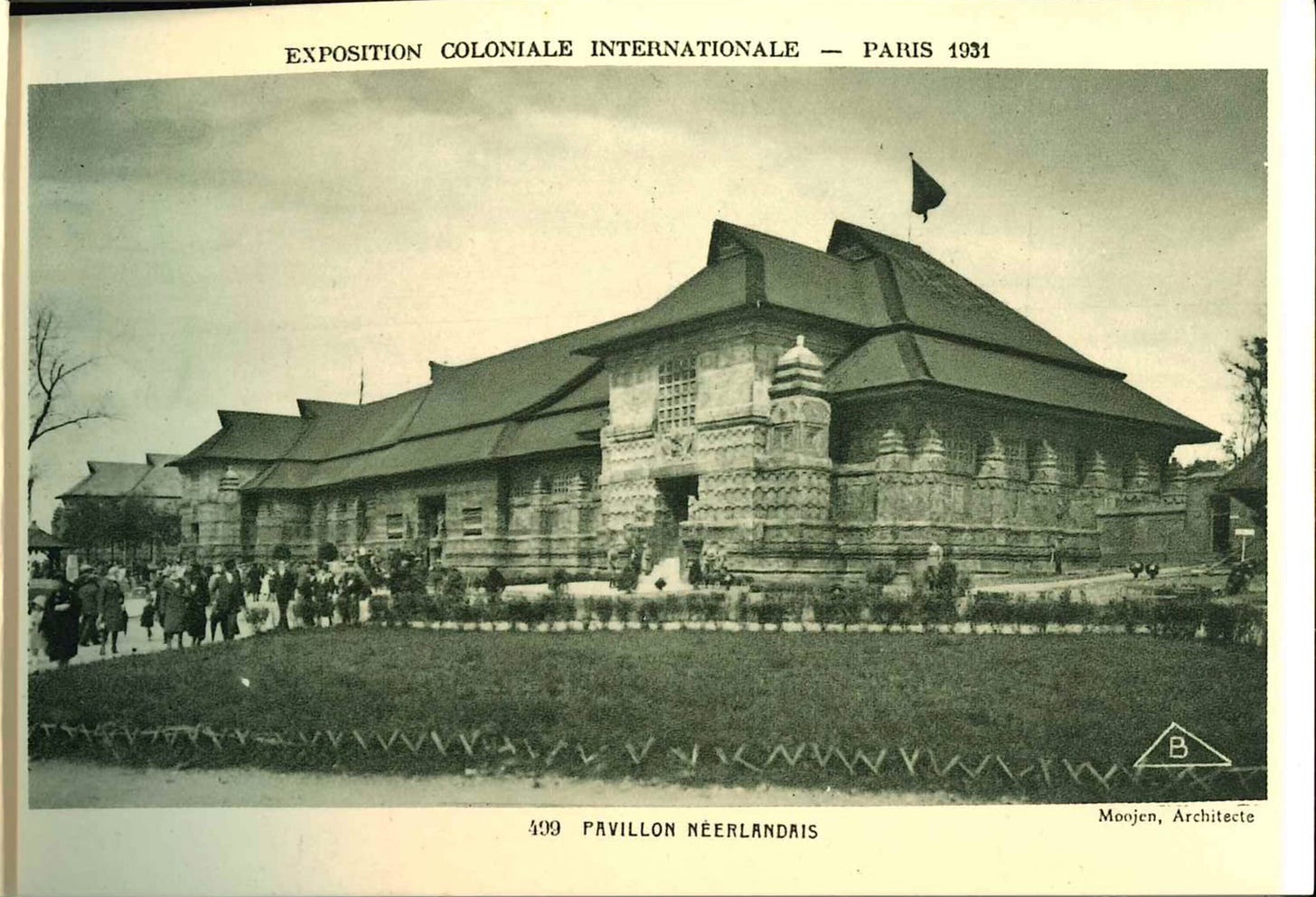

Finally, here is an image of the Dutch Pavilion:

The main pavilion is built in a stylised Malay style [shown in the picture postcard above]. Covering 6,000 m2, it displays collections of Hindu-Javanese art and Buddhas, as well as the economy of the three Dutch colonies: the Dutch East Indies, Suriname and Curaçao. The building is richly decorated with stone sculptures, and is covered by an imposing roof featuring two 50-metre-high towers; a small pavilion houses private exhibitions and a tropical aquarium.

Between the two pavilions is the Place des Indigènes [Square of the Indigenous Peoples], accessed via the Porte de Bali, a monumental carved stone gateway used mainly for dance performances; surrounding the pavilions are houses and boats belonging to the indigenous Batak people.

Back to the French Colonies

Simply because I can, I’m also reproducing some more postcards from the French colonies as I wouldn’t want you to forego these really nice postcards:

Above, an image showing off French Algeria; below, a view of the Moroccan Pavilion.

Behold the Pavilion of Equatorial Africa:

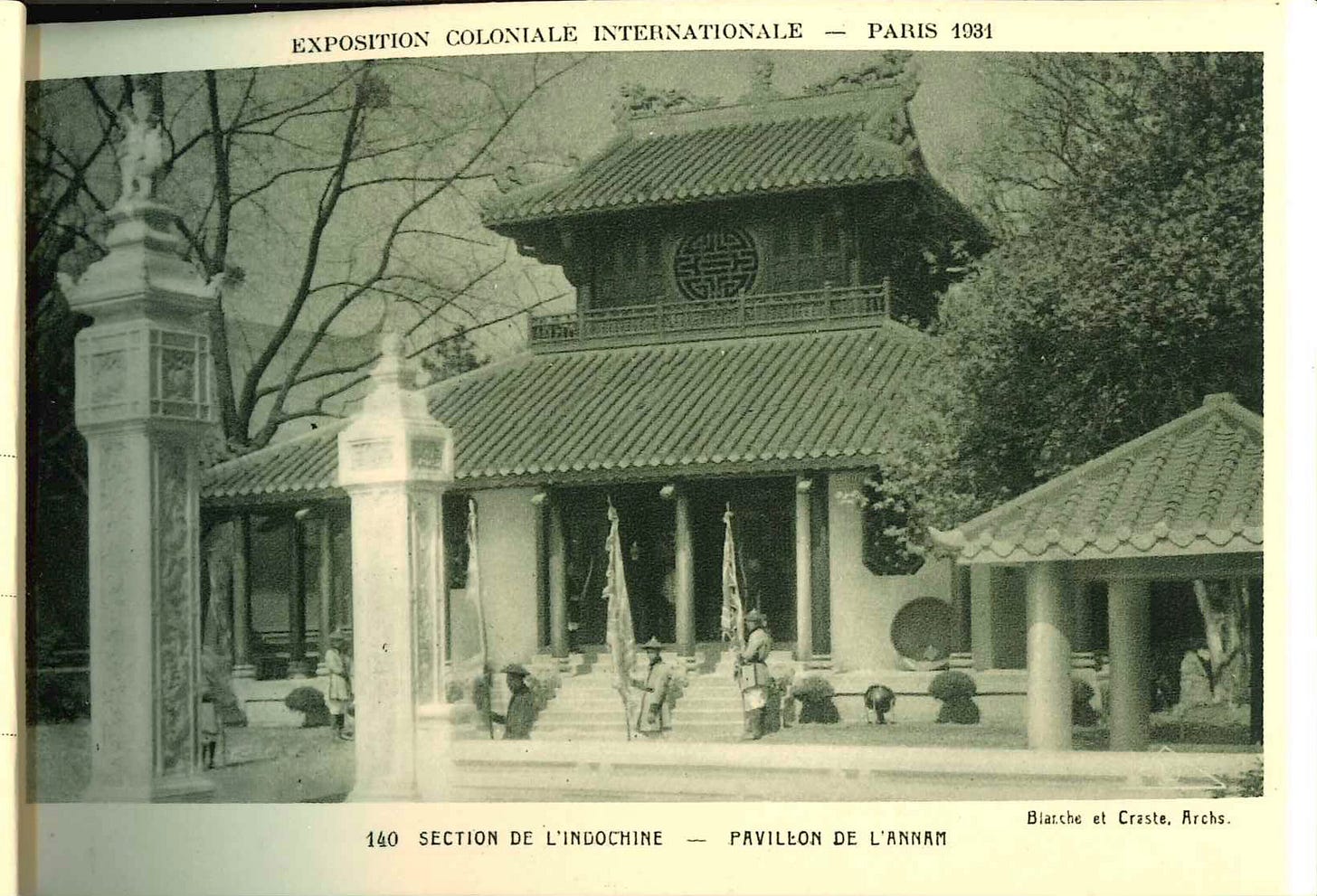

And, finally, to return to Indochina, specifically Annam, is to go back to where our little trip to the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition began:

Post Script: What Remained of the 1931 Exhibition?

I mentioned some resistance to the exposition, and here’s what this is about:

At the request of the Communist International (Comintern), a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth About the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party and the CGTU [France’s Communist Union Federation], attracted very few visitors (5,000 in 8 months). The first section was dedicated to abuses committed during the colonial conquests, and quoted Albert Londres and André Gide’s [a later Nobel laureate (literature), he was also notorious for his pedophilia, including, perhaps ironically, his desire of forcing him on “little Mohammad”, as his Wikipedia entry explains] criticisms of forced labour in the colonies while the second one made a comparison of Soviet “nationalities policy” to “imperialist colonialism”.

Albert Londres, by contrast, was one of the premier investigative journalists of his age and, unlike Gidé, had a less controversial and, frankly, despicable taste.

Back to the 1931 Exposition—and what remained.

As one of the important colonial powers at that time, the Dutch Empire participated in the Exhibition. The Netherlands presented a cultural synthesis from their colony, the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). However, on 28 June 1931, a fire burnt down the Dutch pavilion, along with all cultural objects displayed inside.

As Wikipedia explains—and here I kept the links for you perusal—this is what remains to this day:

Palais de la Porte Dorée, Former-musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie, current Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration, porte Dorée in Paris, constructed from 1928 to 1931 by the architects Albert Laprade, Léon Bazin and Léon Jaussely.

The foundations of the Parc zoologique de Vincennes.

The Pagode de Vincennes, on the edges of the lake Daumesnil, in the former houses of Cameroon and Togo of Louis-Hippolyte Boileau: Photo

The church Notre-Dame des Missions was moved to Épinay-sur-Seine (95) in 1932.

The reproduction of Mount Vernon, house of George Washington, moved to Vaucresson where it is still visible.

The Scenic Railway was moved to Great Yarmouth Pleasure Beach, where it still operates to this day.

And thus concludes our armchair trip to the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition.

Onwards we shall travel, to far-distant lands, before too long.

I'm so glad the US chose to reproduce Mount Vernon. I think it's very pretty.