Hugo Brehme in Yucatán, c. 1920

Part three of our sojourn to Mexico takes us to the remnants of the Mayan civilisation that were just re-emerging out of the jungle

As you may recall, in this armchair trek across Mexico, we encountered a German emigre by the name of Hugo Brehme whose photographs—nay: art—adorns many a postcard in Erich Sonntag’s collection.

While I don’t know how my grandfather ended up in his collection—I know his hobby was known in his circles and he might either have been given these postcards by someone else or “found” them at a garage sale or the like—these are very interesting as I learned about the photographer—artist—who made these images.

Below, I’m linking to the first two instalments of this series, and while there is some information in Hugo Brehme’s English Wikipedia entry (which I cite in the second part), today I’ll provide “more” biographical insights courtesy of his German Wikipedia entry (which comes to you in my translation, with emphases added):

Hugo Brehme was the son of shoemaker Theodor Albert Brehme and his wife Anna Elise Brehme, née Anne Elise Wick. In 1898, Brehme completed a photographic apprenticeship in Erfurt. He was particularly interested in Africa. From 1900 to 1901, he took part in several expeditions to Togo, Cameroon, German South-West Africa and German East Africa. A bout of malaria forced him to return to Germany.

From 1905 to 1907, Hugo Brehme travelled to Mexico, a country that never left him. In 1906, he published his first Mexican photographs in the magazine El Mundo Ilustrado. On 10 August 1908, he married Auguste Karoline Hartmann and moved to Mexico City with her shortly afterwards. In 1914, an attempt by the Brehme couple to emigrate to the USA failed, as their savings were stolen just before their departure and they were therefore unable to raise the necessary surety. In the same year, their son Arno Hugo Brehme was born, and Hugo Brehme opened his photo studio Fotografía Artística Hugo Brehme in Mexico City, which soon became one of the most sought-after in the capital, also thanks to the support of Rodolfo Groth, a businessman and patron from Lübeck. The income from his photo studio enabled Brehme to travel all over the country and his pictures were published in numerous books, most notably in México pintoresco (1923) and in Mexico: Baukunst, Landschaft, Volksleben ([Art, Countryside, Folk-Life] 1925). Brehme also sold his photos as postcards to tourists.

That will do for now—and while I’m very intrigued by this earlier interest of Brehme, we shall look at Yucatán as it presented itself to him now.

Yucatán, c. 1920

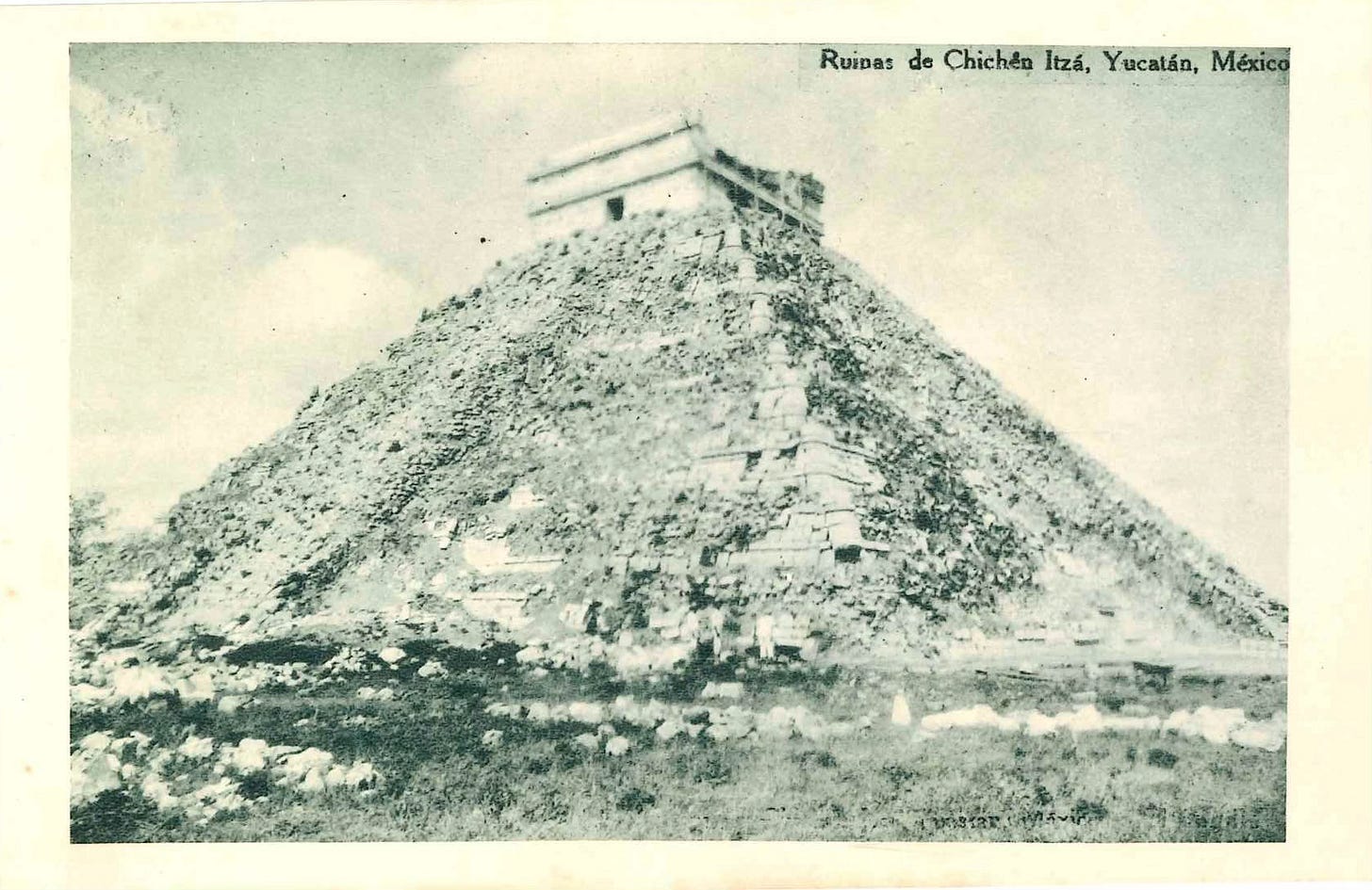

When Brehme travelled the country in the early 1920, he also stopped in the Yucatán peninsula, which was just about to be excavated under the direction of American archaeologist Sylvanus G. Morley (for the below source, click here):

In 1923, the Mexican government awarded the Carnegie Institution a ten-year permit (later extended by another ten years) to allow U.S. archeologists to conduct extensive excavation and restoration of Chichen Itza. Carnegie researchers excavated and restored the Temple of Warriors and the Caracol, among other major buildings. At the same time, the Mexican government excavated and restored El Castillo (Temple of Kukulcán) and the Great Ball Court.

This is the important clue as Hugo Brehme’s below-reproduced photographs show some of the just-excavated Maya sites—before their restoration.

We’ll start with the Temple of Kukulcan at Chichén Itzá (above), also known as El Castillo, and perhaps one of the most iconic monuments of the place.

The below postcard shows a detail of the Temple of Warriors, also known as Tempio de los Guerreros—before moving on to Uxmal.

Uxmal, c. 1920

Brehme not merely stopped at Chichén Itzá, but he also went to the nearby site of Uxmal where he took the below picture of what archaeologists have taken to calling the Nunnery Quadrangle. Below, you can see the so-called “Eastern House”:

The Nunnery Quadrangle was built from 900-1000, and the name related with nuns was assigned in the 16th century because it resembled a convent. The quadrangle consists of four palaces placed on different levels that surround a courtyard. Of the different buildings that make up this palatial complex, several vault tops have been recovered, they are painted and represent partial calendrical dates from 906 to 907 AD, which is consistent with the Chan Chahk’ahk Nalajaw period of government. The formal entrance, the hierarchy of the structures through the different elevations, and the absence of domestic elements suggest that this space corresponds to a royal palace with administrative and non-residential functions, where the ruling group must have had meetings to collect the tribute, make decisions, and dictate sentences among other activities. These set of buildings are the finest of Uxmal’s several fine quadrangles of long buildings. It has elaborately carved façades on both the inside and outside faces.

Mitla, Oaxaca, c. 1920

Mitla is the second-most important archeological site in the state of Oaxaca in Mexico, and the most important of the Zapotec culture. The site is located 44 km from the city of Oaxaca…at an elevation of 4,855 ft (1,480 m), surrounded by the mountains of the Sierra Madre del Sur, the archeological site is within the modern municipality of San Pablo Villa de Mitla. It is 24 mi (38 km) southeast of Oaxaca city…Mitla [was] the main religious one in a later period as the area became dominated by the Mixtec [source].

Friezes like the one shown in the above postcard are…

…the main distinguishing feature of Mitla is the intricate mosaic fretwork and geometric designs that profusely adorn the walls of both the Church and Columns groups. The geometric patterns, called grecas in Spanish, are made from thousands of cut, polished stones that are fitted together without mortar. The pieces were set against a stucco background painted red. The stones are held in place by the weight of the stones that surround them. Walls, friezes and tombs are decorated with mosaic fretwork. In some cases, such as in lintels, these stone “tiles” are embedded directly into the stone beam.

Sayil, c. 1920

Finally, Brehme also stopped in Sayil, another major pre-Columbian site in Yucatán, and photographed what is known as The Grand Palace.

As the horses in front of the ruins indicate, getting there used to be quite a bit of different a century ago.

The Great Palace has an 85-meter-long facade and is built upon a two-terraced platform, giving the impression of three stories. Various rooms are arranged around the four sides of each terrace. The uppermost terrace supports a long structure with a single range of rooms. The palace was built in various phases through an unknown period of time in the Terminal Classic; wings were added and platforms were designed, which were filled with stones and mortar to increase stability. The palace has a central stairway on the south side, giving access to the upper levels of the building.

And with this image, we shall conclude our journey to the Yucatán peninsula courtesy of Hugo Brehme.

I do encourage you to follow the linked content to check out present-day images of these sites.

The Legacy of Hugo Brehme (1882-1951)

I wish to end this piece with a bit more from Brehme’s German Wikipedia entry:

In 1930, a fire broke out in the studio, destroying a large part of the photographic stock stored there.

That is a major shame, yet some of his work survived—in picture postcards like these here—and in old, vintage books that you could purchase via one of my favourite internet sites: the Zentrales Verzeichnis Antiquarischer Bücher, or Central Repository of Antiquarian Books. It’s basically like Amazon or Ebay—for used books (website in German only, but remember: “Suche” means “Search”, Autor = author, Stichwort = keyword, ISBN is self-explanatory).

Keep in mind that postal delivery in continental/German-speaking Europe works like a charm, delivery prices to other areas in Europe are a bit higher (and I have no experience with Transatlantic fees). But it’s an extra-awesome website.

Here’s a direct link to works by Hugo Brehme that are on sale.

From the mid-1920s onwards, Brehme was regarded as the most important photographer of Mexico of his time. His photographs can be categorised as modernist. In his pictures, he captured the typical life of the Mexican people, as well as landscapes and architectural buildings, but also important personalities of the Mexican Revolution. He “repeatedly photographed the indigenous population and was one of the first photographers…to never take a picture without the consent of those photographed—an attitude that was anything but a matter of course at a time when indigenous people were sometimes photographed like objects.”

ZVAB and Abebooks have merged, so you can easily search for German titles from an English interface.

Very nice. Thank you