"Oh, thou my Austria!" Leoben in Styria Through the 20th Century

Part one of a three-part series about a small town in central Austria

Living abroad is an interesting experience—for it changes a lot of perspectives: certain memories become “better” while other issues recede in importance. One of the key experiences in these past fifteen years since I left my hometown, Vienna, is that I seem to “like” Austria better the longer I don’t live there.

Call me a cynic, if you like, but in purely professional terms, I doubt that I’d have spent a decade researching the history of the Habsburg monarchy if I lived in Austria. Half-jokingly, I sometimes refer to the background of my forthcoming book as a way of addressing my own homesickness.

I do think, though, that this rosy image of Austria exists mostly in my head, but one thing is clear to me despite all the changes I witness every time I’m visiting: personal experiences and attitudes may shift over time, but one thing remains: Austria is a country of stunning beauty and many good things (food, for starters), even though I feel more and more like a stranger when I’m physically “there”.

Enough with these ramblings, especially as my exchanges with other expats (in my line of work, it’s quite common to find others who experience comparable issues), this is all but a kind of meandering preface to introduce a three-part series about a place called Leoben, “a Styrian city in central Austria, located on the Mur river. With a population in 2023 of about 25,140 it is a local industrial centre and hosts the University of Leoben, which specialises in mining. The Peace of Leoben, an armistice between Austria and France preliminary to the Treaty of Campo Formio, was signed in Leoben in 1797.” (Source.)

I’ve mostly passed through the town, but when I looked through the postcard boxes, I was stuck by some of the images. Hence, this mini-series, which I hope you’ll enjoy.

Leoben Before and During the Great War

From the above-linked Wikipedia article: “Leoben is located in the Mur Valley, around eight kilometres east of Sankt Michael in Obersteiermark and 15 kilometres west of Bruck an der Mur. The old town centre was founded in the ‘Murschleife’, a meander. Today Leoben stretches on both sides of the river.”

Identification of the time period of the above (and below) postcards is possible by both the way they were produced: coloured after printing, there is but a limited number of colours seen, hence their somewhat ‘artificial’ look. And then there’s the option, as in the reverse of the above postcard, of seeing dates, stamps, or postal marks (or a combination of these):

Above, a view of the Mur bridge and Leoben’s iconic Schwammerlturm (lit. Mushroom-topped Tower); below, with the Mur bridge clearly visible in the centre of the image, a view of the town.

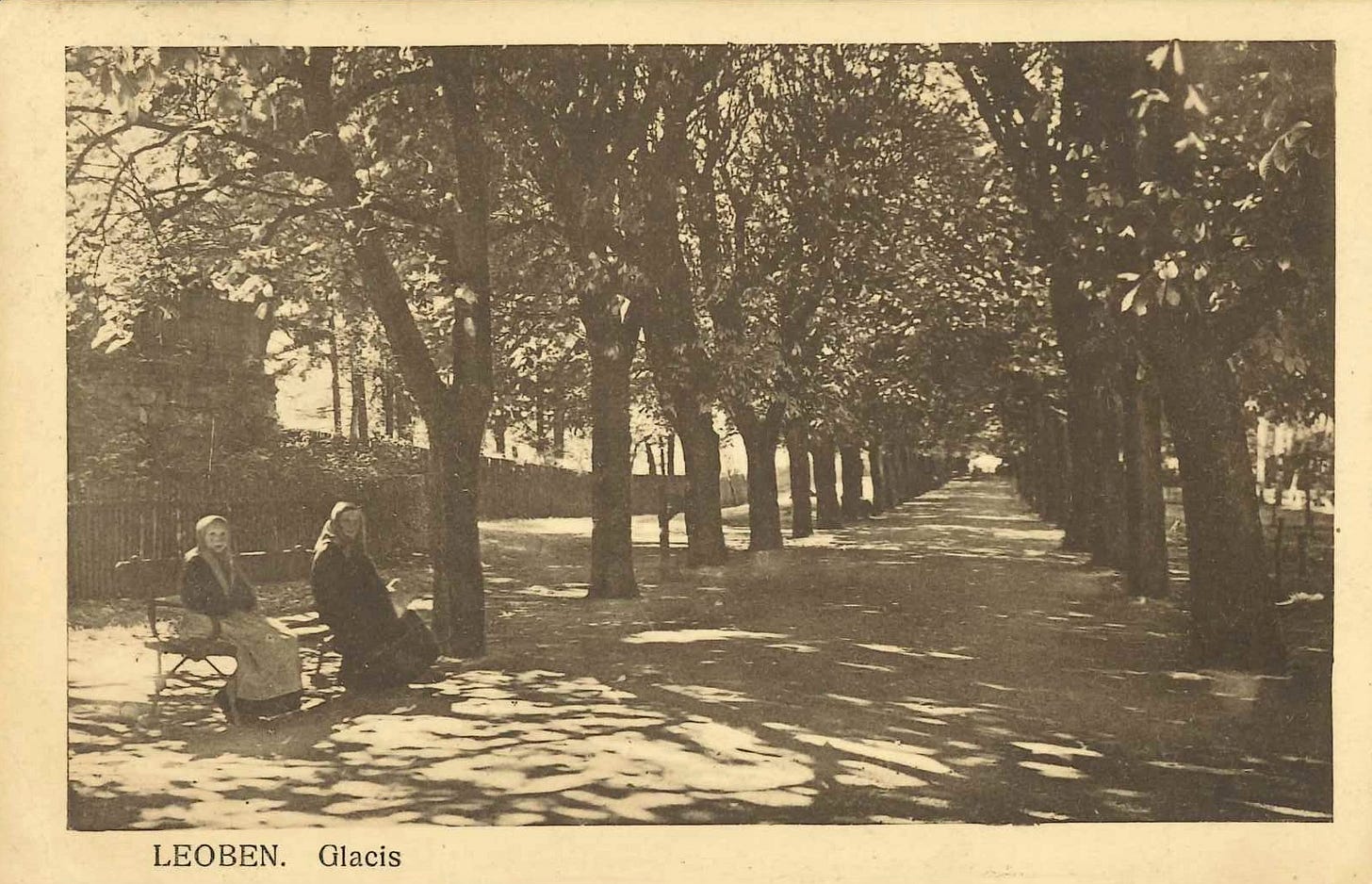

Unlike in, say, North America, many European cities used to have city walls. While these were demolished in the nineteenth century, most cities constructed palaces, public buildings, such as parliaments and university buildings, and parks on the open spaces just outside the walls, known as glacis. Vienna’s magnificent Ringstraße is the perhaps best known example in Central Europe (that is, outside Budapest’s circular road around the old towns), and Leoben, too, has a park, shown above in this postcard.

Below, the Emperor Joseph Square with the Grand Hotel Gärner is shown.

A Final Word About the Title of the Series

The title— “Oh, Thou My Austria”, orig. “Oh, Du mein Österreich”—refers to a military march composed by Franz von Suppé, with lyrics by Anton von Klesheim.

Its translation, cited below (source), was done by none other than John Philip Sousa:

Where snow-crown'd mountains rear their summits t'wards the sky,

As tho' they vonverse held with clouds in Heav'n on high.

Where pure from sparkling springs flow waters crytal clear,

Where chamois fleet are chas'd by youths who ne'er known fear,

|: Who aim, when far above on rocky steep they stand, :|

Yes, that is my Austria! That is my Fatherland!

That is my Austria! My Fatherland!

Yes, there, where Alpine maids the gayest ditties sing,

Where youths the sweetest flow'rs to blushing maidens bring.

Where echoes far and near ring clearly on the air,

Where faith and love go hand and hand in union fair.

|: Ah ! there where faith and love go ever hand in hand. :|

Yes, that is my Austria! That is my Fatherland!

That is my Austria! My Fatherland!

For a modern rendition, Youtube is of great assistance:

We’ll continue to explore Leoben tomorrow. Until then—have a nice Sunday.

Lovely uplifting tune. The masking up towards end made me laugh, as did the 4 soldiers doing Biden impression at the end! Austria is a very beautiful country.

Leoben 2

Neben der Erzbergbahn und dem legendären und charakteristische Schwammerlturm, gut zu sehen auf der Murbrücken-Postkarte der Erich-Sonntag-Kollektion und von Stephan Sander-Faes einfühlsam übersetzt mit „Mushroom-topped Tower“, assoziiere ich mit dem Leoben der Vorkriegs-, der Kriegs- und der Nachkriegszeit die unvermeidlichen Hochöfen von Leoben-Donawitz. Neben dem Eisen, das vom steirischen Erzberg abgebaut wurde und wird, fiel in Leoben in (bis 1924) abbauwürdigen Mengen ein weiteres Produkt an, das in der steirischen Kriminalgeschichte eine große Rolle spielt: Während im Hochofen das geschmolzene Eisenerz nach unten rann und zu Stahl weiterverarbeitet wurde, schlug sich an den Hochofen-Innenwänden der „Hüttenrauch“, steirisch „Hittrach“ genannt, nieder, chemisch gesehen das Element Arsen.

https://www.steiermark.com/de/Erzberg-Leoben/Urlaub-planen/Urlaubserlebnisse-suchen-buchen/Sonderfuehrung-der-voestalpine_asd_11246258 . Arsen diente einerseits dem Betrugswesen (unseriöse Pferdehändler verwandelten mit Hilfe des kurz aufputschenden, aber bald fatal seine Giftseite zeigende Arsens jeden alten Klepper in einen feurigen Hengst). Andererseits wurde Arsen in der Steiermark gern zur Regelung (sprich: Beschleunigung) sich allzu lang hinziehender bäuerlicher Erbfolge herangezogen. Zwei steirische Volksmundbegriffe beschreiben die einschlägige Vorgangsweise ziemlich präzise: „Hittrachieren“ bezeichnet den Einsatz von Hüttenrauch zu oben angeführten Zwecken. Aber auch das beinahe liebevolle „Ahnl-Vergiften“ fand Eingang in den Sprachgebrauch. Siehe auch: https://www.uibk.ac.at/irks/publikationen/2020/pdf/arsenesser.pdf

Der letzte mir bekannte Arsen-Mord in der Steiermark betraf 1972 den seinerzeitigen Grazer Turniertanz-Weltmeister Heinz Kern, der den Genuss einer stark arsenhältigen Verhackert-Jause nicht überlebte. Im Volksmund bürgerte sich für den schmackhaften Schweinefettaufstrich „Verhackert“ https://de.wiktionary.org/wiki/Verhackert ersatzweise die makabre Bezeichnung „KERN-Fett’n“ ein. Als junger Kriminalreporter berichtete ich über den (bis heute ungeklärten) Arsenmord an Heinz Kern in der Grazer „Kleinen Zeitung“