Old Vienna (Before WW2)

To compare the images of war-damage, what better way would there be than to look at some pre-1939 picture postcards of my hometown?

The answer to the above-related quip being perfectly obvious, here’s a bit more “background” on today’s posting: while I was rummaging through the boxes labelled “Vienna”, I didn’t find “just” the below-referenced images of the war-torn city:

I also found a booklet with some 20 picture postcards unceremoniously labelled “Images of Vienna” (orig. Wiener Bilder), some of which I shall share today.

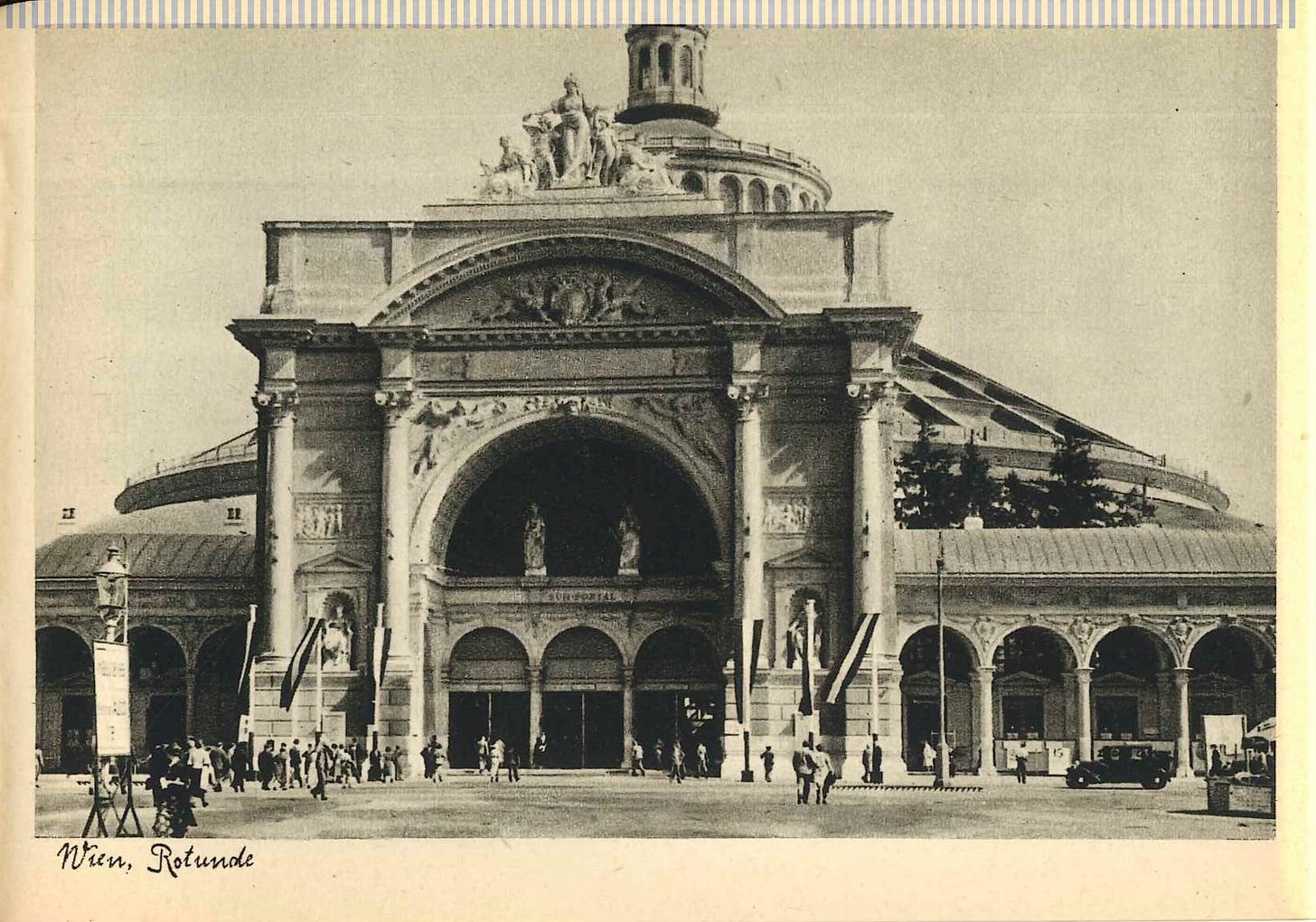

One last word about these images, esp. their dating: there is one particular picture that permits a kind of approximate determination, and I reproduce it below:

It shows the so-called Rotunde, or Rotunda, which was destroyed in 1937—hence these pictures were made

The Rotunde (German: [roˈtʊndə]) in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district was a building erected for the 1873 Vienna World's Fair (German: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien)…While the Rotunda stood, its dome was the largest in the world, larger than the Pantheon in Rome.[b] Not until 1957, 20 years after the Rotunda fell, was a larger dome built: the dome of Belgrade Fair – Hall 1, which is only about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) larger in diameter…

The Rotunde burned down in 1937. Its former site is now occupied by buildings associated with the Vienna University of Economics and Business, and with Messe Wien.

With that serving as an introduction, let’s explore some of the other imagery of Old Vienna, or Alt-Wien, shall we?

Sights and Marvels of Old Vienna

While I have no problem sharing the main sights, I’d rather post some of the less-known places for the sake of them being, well, a bit more representative of my home town how it once was.

We’ll start at the New Market, or Neuer Markt, which we also mentioned in the Spring 1945 posting.

When the High Market [orig. Hoher Markt] was no longer sufficient to supply the Viennese population in the Middle Ages, the New Market was created, which was first mentioned as nuiwe market or novum forum in 1234. As flour and grain were also traded here until the 19th century, the square was unofficially known as Mehlmarkt (flour market), a name that stuck until the 20th century. The square was severely damaged during the Second World War and a number of buildings disappeared and were replaced by modern structures.

Behold a view of the New Market before the Second World War:

The Donnerbrunnen fountain in the centre of the square was created by Georg Raphael Donner in 1739. Its real name is Providentiabrunnen, it is also known as Mehlmarktbrunnen. The bronze sculptures are copies, the originals are in the Vienna Museum. The short Donnergasse, which connects Neuer Markt with Kärntner Straße, was named after the sculptor.

The most famous building on Neuer Markt is the Capuchin Church, which was completed in 1632. Beneath it is the Capuchin Crypt, the resting place of the Habsburgs.

Next up, a view of Vienna’s main avenue in the city centre, the so-called Graben (literally “moat”) with the Plague, or Trinity Column (Dreifaltigkeitssäule), erected in the wake of a late 17th-century plague by the emperor Leopold I (r. 1658-1705):

Erected after the Great Plague epidemic in 1679, the Baroque memorial is one of the best known and most prominent sculptural artworks in the city. Christine M. Boeckl, author of Images of Plague and Pestilence, calls it “one of the most ambitious and innovative sculptural ensembles created anywhere in Europe in the post-Bernini era.”[1]

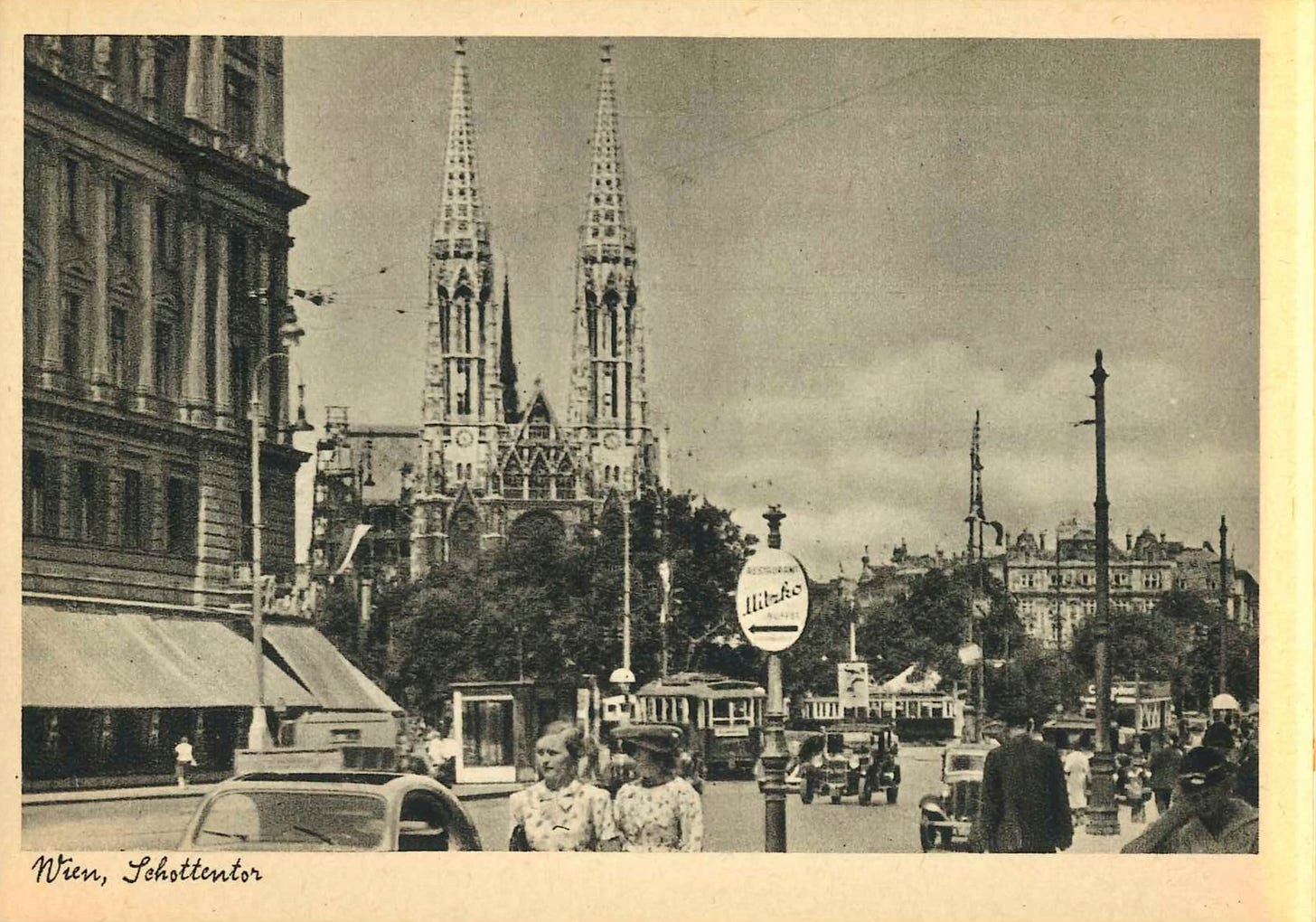

Next up, a street view-esque image of the Schottentor, once the location of one of Vienna’s gates—Schottentor translates literally into “Scots’ Gate”, albeit not because of many Scots who once lived there…but because “the names Schottentor and Schottengasse (the name of the old town alley leading to the gate) go back to the Schottenstift monastery that bordered the alley”. Today, the area is one of Vienna’s main public transport hubs and a much-frequented area of town.

By the way, as per the Schottenstift’s Wikipedia entry, here’s another fun anecdote:

The Schottenstift (English: Scottish Abbey), formally called Benediktinerabtei unserer Lieben Frau zu den Schotten (English: Benedictine Abbey of Our Dear Lady of the Scots), is a Catholic monastery founded in Vienna in 1155 when Henry II of Austria brought Irish monks to Vienna. The monks did not come directly from Ireland, but came instead from Scots Monastery in Regensburg, Germany.

The church seen here, however, isn’t the Schottenstift but the so-called Votivkirche,

a neo-Gothic style church located on the Ringstraße in Vienna, Austria. Following the attempted assassination of Emperor Franz Joseph in 1853, the Emperor’s brother Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian inaugurated a campaign to create a church to thank God for saving the Emperor's life.

And here’s how that one transpired according to lore and tradition:

The origin of the Votivkirche derives from a failed assassination attempt on Emperor Franz Joseph by Hungarian nationalist János Libényi on 18 February 1853.[2] During that time, when the Emperor was in residence at the Hofburg Palace, he took regular walks around the old fortifications for exercise in the afternoons. During one such stroll, while walking along one of the outer bastions with one of his officers, Count Maximilian Karl Lamoral O’Donnell von Tyrconnell, the twenty-one-year-old Libényi attacked the twenty-three-year-old Emperor from behind, stabbing him in the collar with a long knife. The blow was deflected by the heavy golden covering embroidered on the Emperor'‘s stiff collar.[2] Although his life was spared, the attack left him bleeding from a deep wound.[3]

A civilian passer-by, Dr. Joseph Ettenreich, came to the Emperor’s assistance, and Count O’Donnell struck Libényi down with his sabre, holding him until the police guards arrived to take him into custody.[3] As he was being led away, the failed assassin yelled in Hungarian, “Long live Kossuth!” Franz Joseph insisted that his assailant not be mistreated. After Libényi's execution at Spinnerin am Kreuz in Favoriten for attempted regicide, the Emperor characteristically granted a small pension to Libenyi’s mother.[3]

Dr. Ettenreich, who quickly overwhelmed the attacker, was later elevated to nobility by Franz Joseph for his bravery, and became Joseph von Ettenreich.[4] Count O’Donnell, who up until then was a count in the German nobility by virtue of his great-grandfather, was afterwards made a Count of the Habsburg Empire and received the Commander's Cross of the Royal Order of Leopold.

The lesson of history is as clear as obvious: save the monarch’s life, become a noble.

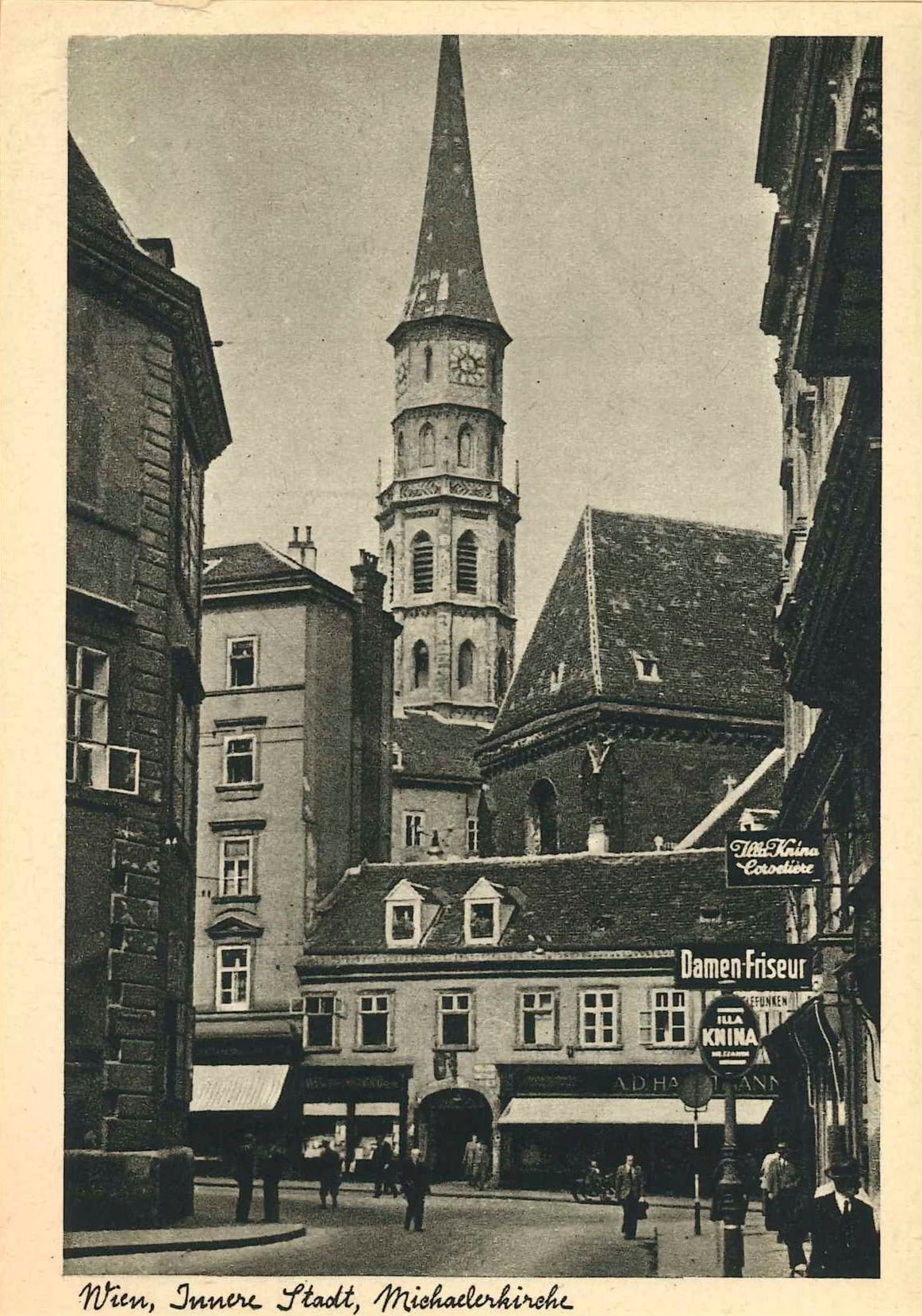

[EDIT due to a little confusion] Next up, “Saint Michael’s Church (German: Michaelerkirche) is one of the oldest churches in Vienna, Austria, and also one of its few remaining Romanesque buildings. Dedicated to the Archangel Michael, St. Michael’s Church is located at Michaelerplatz across from St. Michael’s Gate at the Hofburg Palace. St. Michael’s used to be the parish church of the Imperial Court, when it was called Zum heiligen Michael.”

And then there is the Crypt (for the above info and the paragraphs below, see here):

St. Michael’s is famous for its Michaelergruft, a large crypt located underneath the church. Aristocrats were able to access their family crypts through marble slabs marked with their coats of arms in the church floor. The coffin of a deceased member of the family could then be lowered directly into the crypt via these marble slabs.

Due to the special climatic conditions and constant temperature in the crypt, more than 4000 corpses were kept well preserved. Hundreds of mummified corpses, some still in burial finery or with a wig, are on display, some in open coffins, adorned with flowers or skulls, others decorated with Baroque paintings or with vanitas symbols. The most famous among them is Pietro Metastasio (1698–1782), the most famous writer of opera librettos of the baroque era.

No wonder Old Vienna had that little morbid touch, eh?

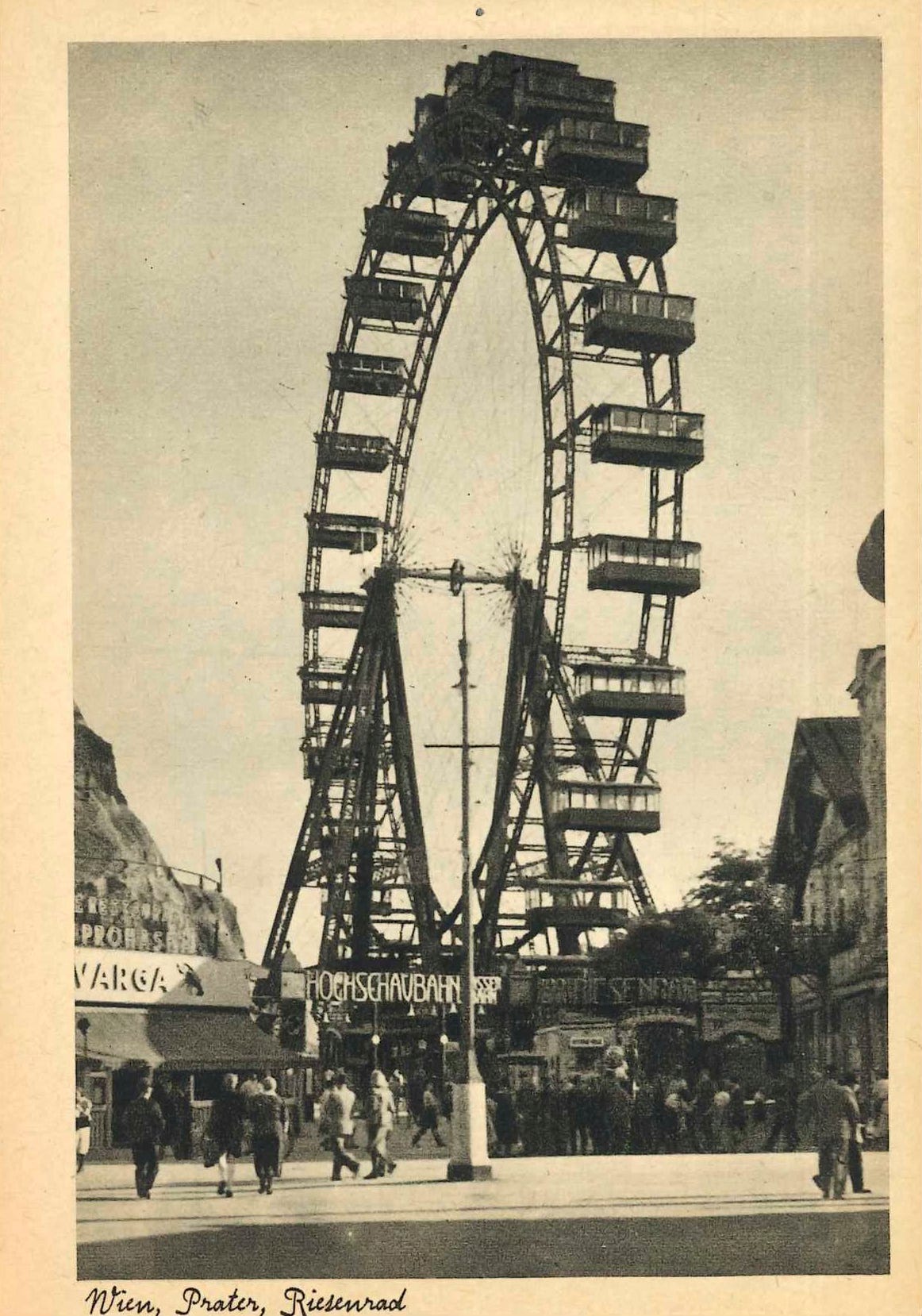

I’ll wrap up this posting with an image of the Riesenrad, of the Giant Ferris Wheel, in the Prater, Vienna’s prime recreational park:

The Wiener Riesenrad…is a 64.75-metre (212 ft) tall Ferris wheel at the entrance of the Prater amusement park in Leopoldstadt, the 2nd district of Austria's capital Vienna. It is one of Vienna's most popular tourist attractions, and symbolises the district as well as the city for many people. Constructed in 1897, it was the world’s tallest extant Ferris wheel from 1920 until 1985.

It was this scenery that was immortalised in Carol Reed’s 1949 classic film noir ‘The Third Man’ (featuring Orson Welles, among others), and I’ll conclude here by re-posting the trailer and to, once again, connect this posting to the previous one: